Ben Moon / The British rock climbing legend interview

1 / 20

1 / 20 Ben Moon archive

Ben Moon archive

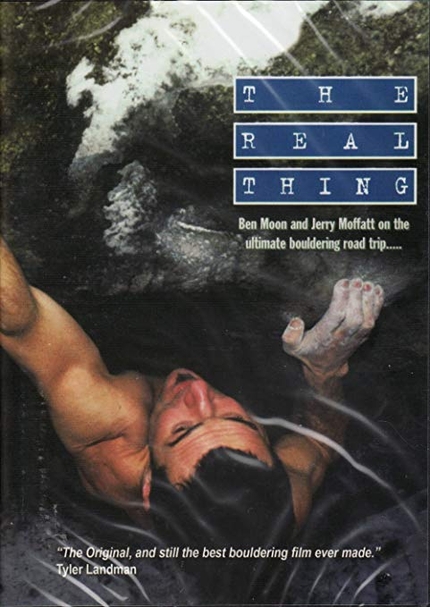

Born in 1966, Ben Moon is one of the leading climbers of his generation who played a decisive role in shaping the face of sport climbing and bouldering throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s. As the sport developed from its embryonic beginnings, in less than a decade Moon pioneered climbs from 8a all the way to 9a, leaving his mark like few others before or since.

After taking up climbing and serving, as was the norm in the early 80’s, a trad climbing apprenticeship, aged 16 he left his home in London and moved north to Sheffield, the epicentre of British climbing, in order to join a small group of climbers who would do almost anything to climb full-time. Living off unemployment benefits and often climbing together with Jerry Moffat, in 1984 eighteen year old Moon shot onto the British climbing scene with his first ascent of Statement of Youth at Lower Pen Trwyn in North Wales; graded 8a, this climb proved groundbreaking both in terms of difficulty and style, as in those days fully bolted sport climbs simply did not exist in Great Britain. Dave Cuthbertson’s masterpiece Requiem, climbed a year earlier up at Dumbarton Rock in Scotland, is considered on a par difficulty wise but since this is a trad climb, Statement of Youth is recognised as heralding the true start of the sport climbing revolution in Great Britain. Even today it is considered one of the UK’s most coveted sport climbs.

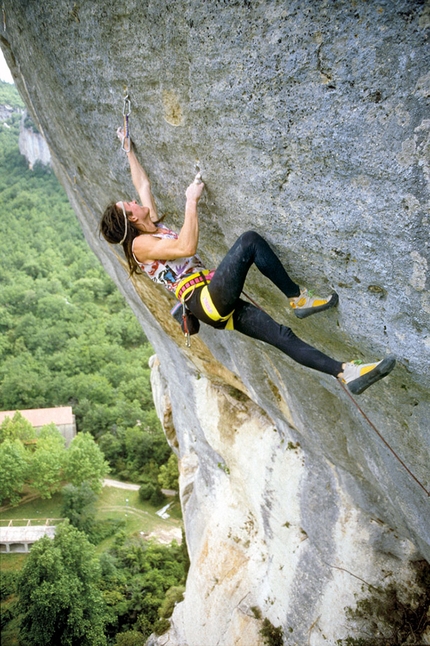

Moon’s tenacity and drive, coupled with new redpoint strategies which proved considerably more efficient than the far slower yo-yo style, resulted in standards rocketing on a yearly basis. After having repeated all the hardest sport climbs in France - in particular the big three Buoux 8b+ La Rage de Vivre by Antoine Le Menestrel, Le Minimum by Marc Le Menestrel and Le Spectre du Sur-Mutant by Jean-Baptiste Tribout - in early 1989 Moon with his hallmark dreadlocks made the first ascent of Agincourt, the first 8c in France and one of the first 8c’s in the world.

A few months later he doubled this up with France’s second 8c, Maginot Line (also referred to as Le Plafond) at Volx, and these paved the way for the pinnacle of his sport climbing career, Hubble at Raven Tor in early 1990. With a Font 8B+ section followed by a 7c+ route, this extremely bouldery limestone testpiece is celebrated as the world’s first 8c+, although it must be said that in its 30-year history it has only been repeated 6 times - and attempted unsuccessfully by many of the world’s best - giving rise to healthy speculation that it may well be graded 9a. Should this be the case, then it would mean that Moon skipped a full grade, going directly to 9a from the world’s first 8c, Wolfgang Güllich’s Wallstreet in the Frankenjura. Interestingly, it would also mean that the world’s benchmark 9a, Action Directe climbed in 1991 by Wolfgang Güllich would no longer be considered the first of its grade. History has a tendency of being rewritten and further repeats are needed to reach consensus.

In 1993 Moon retuned to Lower Pen Trwyn to make the first ascent of the 8c+ Sea of Tranquility and he also set his sights on an even harder project still, the enormous overhanging North Buttress at Kilnsey crag. This intense line of crimps required a new level of power and resistance and after a series impressive attempts, injuries forced Moon to abandon the line which was eventually freed at 9a in 2000 by Steve McClure.

During Moon’s heyday he also devoted much time to hard bouldering and this resulted in a flurry of hard first ascents such as Black Lung (Fb 8B) in Joe’s Valley, USA, Cypher (Fb 8B) at Slipstones and his showpiece Voyager (Fb 8B+) at Burbage in 2006. In 2015 he proved that age is no barrier to hard sport climbing and, aged 48, he climbed the 9a Rainshadow at Malham Cove, while in 2018 he made a rare repeat of the fierce 8c+ Evolution at Raven Tor, England.

In between one hard ascent and the next Moon has managed to devote time to his family and also his business, Moon Climbing which specialises in climbing clothing, equipment and of course the highly-prised Moonboard training wall. Much like the campus board invented by his peer Wolfgang Güllich, Moonboards have become a standard piece of training equipment in many of the world’s climbing walls and offer climbers across the globe the chance to climb identical problems. While few can say they have climbed one of Ben’s routes outdoors, they can at least try their luck on his Moonboard benchmarks indoors. Here’s our interview with the British climbing legend.

Ben, can you take a step back in time and tell us how it all started, and give us an idea about what it was like climbing in the UK in the early 80's?

I left home when I was 16 and moved to Sheffield when I was 17. I look back on those early teenage years as some of the best. Since about the age of 14 I was totally obsessed with climbing but could only go a couple of times a year. Once I left school, home and moved to Sheffield I could climb every day and that’s pretty much all we did. There were no climbing walls at this time (1983) so we climbed outside wherever we could, whatever the weather. The only money I had was what the government paid me, which was about £40 per 2 weeks. This was less than my friends because I was under 18. I lived out of a rucksack and climbed wherever the lifts went. It was total freedom and I learnt a lot about climbing in these early years. The hardest route I had climbed in 1983 was around E3 (maybe 6b+) and by the summer of 1984 I had climbed Statement of Youth. In 1985 I made the 3rd ascent of Chouca in Buoux which at that time was graded 8b. It was a very special period of my life.

So tell us about the aptly named Statement of Youth, which you established when you were just 18. It was hailed as Britain’s first 8a, the hardest climb in the country.

Thanks but I’m not sure that’s quite correct really. A year earlier Dave Cuthbertson had climbed Requiem at Dumbarton Rock in Scotland, which is a trad route past 8a climbing. I’d just say Statement was one of the first 8a’s in Britain in 1984. It was considered one of the hardest rock climbs in the country, but the reason why it made so much noise wasn’t only because it was so hard, but because I’d placed six or seven bolts on it. It wasn’t an aid climb before I did it, it was a completely new line that then happened to become one of the hardest in the country. When I first stood beneath Statement of Youth I did consider protecting some sections with trad gear, but then I thought it would be ridiculous and decided to bolt it all up. Which is what I did. So in many respects it was the first proper, hard sports climb in the country.

What’s important to understand is that back in the early 1980’s bolts were pretty new and, in Britain in particular, not particularly appreciated.

Yes very definitely. In 1984 sport climbing simply didn’t exist in Britain. All routes were either trad routes or as I mentioned, aid climbs that had subsequently been freed. There were some routes about in the UK which had pegs or bolts, but the bolts were aid climbing bolts which tended to all be very old and rusty, and not very safe. Sport climbing as we know it nowadays didn’t exist in 1984 and Statement of Youth was one of the first sport climbs in the country. So yeah, it was quite controversial.

Did you expect the controversy?

Not really. All the peers I was climbing with at the time sort of knew that sport climbing was coming. Jerry Moffat, myself and others, we’d all climbed in France in the previous years and had seen what was going on in Europe. The standard had started to rocket on the continent and trying to push the standards at home with trad climbing only wasn’t going to be practical.

You mentioned Jerry. The two of you were quite a team!

Jerry doesn’t climb any more, which is a shame, but we’re obviously still in touch. Some of his routes are up among there as the very best in the country, definitely. An absolutely amazing climber.

Most of your trips to France were all the way down to Buoux.

In the mid-eighties Buoux was the world’s main forcing ground for sport climbing, with people like the Le Menestrel brothers, Patrick Edlinger and plenty of others all doing hard first ascents in Buoux. Routes in the 8b, 8b+ range. It was the obvious place to go and test ourselves.

And to leave your mark, above all with Agincourt, France’s first 8c.

During a 10-day period in 1988 I repeated La rage di Vivre, Le Minimum and Le Spectre, which at the time were the hardest routes in Buoux and among the hardest in the world. I was in good shape. Agincourt was still an old aid route and I knew a few of the French climbers had had a look at it. It was an open project, someone had put a few bolts in and I thought I’d give it a go in November that year, and eventually did it in January 1989.

That sounds pretty quick!

Actually I didn’t do it that quickly, certainly not as quickly as Didier Raboutou when he repeated it! In November 1988 when I first started trying it I probably spent about 12 days trying it. At first I figured out a way to the right of the aid climb, then a friend of mine found a better way to the left and that’s the way I ended up doing it. But I had to come back in January 1989 for the redpoint. I think I did it on my second day that January, but if you add to that the 12 days in 1988 it wasn’t really that quick.

To be honest though, a fortnight doesn’t really sound that long to establish something which at the time was at the absolute apex. Wolfgang Güllich had been the first to climb 8c with his Wallstreet in the Frankenjura in 1987, but there still weren’t too many 8c’s around. And certainly not in France! If someone put up a 9c in just two weeks now, surely that would be considered quick.

I suppose that’s true, but back then it felt like a lot. I didn’t spend too long on Hubble either, again about 10 days in total, of which two the year before my redpoint. Up until Northern Lights I’d never really spent that long trying a route. Big long sieges are probably more of a modern thing, and I myself do them now, too. Back then though we didn’t seem to spend so long on just one project.

Wolfgang had put up Wallstreet a few months before you did Agincourt. What was the reaction at the time to the world’s first 8c?

I can’t remember to be honest when I first heard about Wallstreet, internet didn’t exist. I remember the fact that Wolfgang climbed it and gave it a German grade, and later filled it some holds after he felt it had been chipped, making it harder in the process. It’s definitely considered 8c, the first 8c in the world. I tried it once when I was in Germany. It seemed hard. Very very bouldery.

Buoux is no longer as popular as it once was, but sooner or later it will be back in the limelight with the famous Bombé bleu project bolted by Marc Le Menestrel, which has been tried by many of the world’s best, including you.

Yes, that’s true, in 1990 probably. It seemed really really hard, really futuristic. Deep down inside I probably thought it wasn’t possible really, for me at least, although I did take some moulds of the pockets and made a replica back in the UK. I never succeeded on the replica. I did read about a few people trying it and doing all the moves which I was quite surprised to hear. It would be good to see someone finally do that route! It’s been there for a long time.

In 1990 you were on top form though and made the first ascent of Hubble at Raven Tor, presumably your masterpiece

Well it’s probably not my best route, but I suppose in terms of difficulty you could define it as such.

So what would you consider your best route then?

Hard one that! Statement of Youth is a route I’m pretty proud of. It’s not like it’s the hardest, but it’s a real classic. It’s the one that everyone want’s to do, if you climb 8a and live in the UK. It’s a great line and has a great history.

Back to Hubble then, which you climbed in June. At the time it was hailed as the world’s first 8c+. Possibly though it’s even more.

Yes. Certainly. Well I think it definitely is more, everyone seems to have accepted that, Adam Ondra said it felt like 9a, in the new guidebook it’s been described as being 9a. It’s just another level compared to 8c+ really. It still doesn’t get many ascents.

Perhaps even more time is needed. and when it gets more repeats there’ll be greater consensus. Let’s just imagine though that it really is 9a: that’s quite a leap all the way from 8c to 9a, skipping out 8c+ altogether!

A very big leap, yes. I suppose that’s one of the reasons I probably didn’t even consider giving it 9a when I climbed it. Jumping two grades wouldn’t have seemed right really. When you’re climbing at the absolute limit it’s very hard to tell what that limit represents. If something feels harder than something else, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a full grade harder, it could just be top end of that grade. Grading is really hard basically. And like I said, it didn’t actually take me that long. About 10 days in total, of which only 6 in 1990 when I did it. Things just came together really quickly. In a way I didn’t really realise I’d done something particularly special, it only settled in years later.

Is that speed down to the fact that it really suited your style of climbing?

I’m probably more strength orientated, although I reckon my endurance is pretty good. But Hubble is effectively a boulder problem, it’s 6 moves long, probably about 8B/8B+ boulder problem grade, so if you’ve got the strength you’re likely to do it quite quickly. So yeah, it probably did suit me.

Is it true you had a replica on your board in your cellar?

Yes I did, but it was way too easy so wasn’t any use. Hubble is essentially a very hard 6 move boulder problem straight off the ground. After the boulder problem you do a route 7c+ which you shouldn’t fall off from, although I did. I think I was so shocked to find that I had climbed through the boulder problem that I just went to pieces mentally! I took a rest day and did it the next day. Incredibly that is 30 years ago. The sequence hasn’t changed although the holds might be a little more polished which will add a little extra difficulty.

Out of interest, have you ever repeated any of your hard routes?

Only Maginot Line, back in 1992 before going out to try Action Directe.

Which actually leads me nicely to the next question, Action Directe, the route described as the world’s benchmark 9a.

Well Wolfgang did it in 1991, the year after I did Hubble, and I went to Germany in April 1992 to try it. It was hard, for sure, but I thought it was a similar difficulty to Hubble. I remember having a telephone conversation with Wolfgang about it, he was obviously interested in my opinion and how Action Directe might compare to Hubble. He was keen on coming to try mine but unfortunately he had that tragic car accident. I spent 5 days on Action on that trip, 3 days working it and 2 days redpointing it and got pretty high, to the bit where you traverse left at the top before the finish.

Pretty high? That’s really high!

Yeah but then unfortunately I got injured. It was incredibly cold when we were there, with little snowstorms blowing through. Conditions were actually good but it was really hard to keep your fingers warm, possibly that’s one of the reasons why I got injured. I returned in September that year to try it again but my finger started hurting as soon as I got back on, and I haven’t been to try it since.

Would you be interested in going back?

I’d love to try it one more time, to see how it feels now. Funnily enough I was watching some videos of it on youtube recently, over the years it’s had quite a lot of ascents, better sequences have been worked out, certainly in the middle section where there was a really tricky move which people are doing in a different way. And in fact the place where I fell off on the redpoint is being done differently, too. So yes, I would be keen to try it again.

It’s interesting that on a route with so few moves, new sequences were found

It’s always been like that, with people refining moves, over time sequences evolve and become better and more efficient. That’s how things go in climbing.

Talking about sequences. What about Northern Lights? That’s quite a sequence of moves…

Yes it is! Northern Lights at Kilnsey is a route I first started trying in 1993, I spent about 30 days over the next three years trying to do it. Again, originally an old aid route, then Mark Leach put some bolts in and after Hubble I looked around for something new. I failed to repoint it and in the end gave up, then Steve McClure contacted me in the late '90’s asking whether it was an open project and I told him he was welcome to try it, especially since I'd given up sport climbing at the time and was just concentrating on bouldering. He climbed it in 2000 and gave it 9a, although personally I think it’s 9a+. Steve found a slightly different sequence to mine, possibly slightly easier but still very hard indeed: at about 12 meters I’d make a move right, he actually moved left, so about 3 or 4 meters of different terrain, but still really hard. Having got back into sport climbing I’ve been trying it again, and have invested another 3 years perhaps and have got quite close but not quite managed to do it yet. I’m up to about 90 days on it I think. So if you compare it to my other routes, it’s certainly a massive project for me.

Are you still having fun on it?

Yes, it’s an amazing route, I really love it. Kilnsey is a frustrating place to have a project because conditions are very fickle, both because of the weather and the fact that the crag can seep for no apparent reason, which has stopped me a few times. But to be honest the route is one of the best I’ve ever been on anywhere, it’s such a pure, direct line. After the first 3 or 4 easy meters you’re straight in to the hardest move on the route, and then from there to the top it’s like non-stop, with maybe only two places where you can chalk up. And it’s borderline whether it’s even worth chalking up because it's so hard to stop, and hard even to clip the quickdraws. It’s like an 800m sprint. It takes about 3 minutes to climb and it’s really really sustained at a certain level, around the Font 7B+/7C mark I’d say. It’s a cool route.

You recently said you’re on great form. You're 53. You’re certainly not old, but you’re not the youngest either and have been climbing hard for many, many years.

It’s amazing, but I really do feel on form. My strength isn’t as good as it was when I was younger, perhaps I’m 10 or 15% weaker than what it was in the past, but my endurance feels really good, My weight’s not changed, I don’t have any serious injuries and I just feel like I’m climbing really well. Perhaps I’m lucky with my genes!

No serious injuries after all these years climbing hard, that’s quite an art

A lot has changed in the sport in the last 30 years, there’s an incredible amount of knowledge out there now. I’ve obviously been training for a long time and I feel a lot wiser than I was when I was younger, maybe a little more sensible, too.

What’s one of your greatest assets do you think?

My motivation. It all boils down to that. If you’re not motivated, you’re not going to get anything done regardless of how good you are. Of course I’ve not always been super motivated, for example for the first 5 years or so after my daughter was born I was less keen, but that’s normal, motivation goes up and down but the important thing when you’re not super motivated is to hang in there and keep going until your motivation returns.

Your greatest weakness?

Errm let me think. Perhaps my memory?

You’re still completely clued up about climbing. Does anything surprise you nowadays?

Well the level of the top climbers, in particular Adam Ondra, is unbelievable really. I’m quite experienced about hard climbing, certainly up to about 9a level, but 9b, 9b+, 9c… it’s mind boggling really. The strength and fitness level of the best climbers in the world is just incredible.

Talking about strength. Do you think climbers are a lot stronger then you guys were in the ’80’s and ’90's?

Yes I do. A lot stronger and also a lot fitter. Very impressive indeed. I mean, to do some of these really hard routes they’re doing Font 8b+ boulder problems after having already climbed a 9a route, it’s amazing.

1-5-9. What does this represent? And what did it mean to you guys back then?

Well I haven’t actually done 1-5-9! The original Campus Board which I built in my back garden in 1991 was only high enough for 1-5-8.5 but we just called it 1-5-9 because there were 9 rungs" Regardless it was still pretty tricky to do and back then not many people could do it. I don’t know how much it helped your climbing but it certainly gave you a lot of confidence. But climbing is a very technical sport and I sometimes think those early teenage years climbing on all types of rock were more beneficial than all the years training. I don’t know, if you have the time it’s good to be as diverse as possible. That’s what I mean when I say Train Hard, Climb Harder!

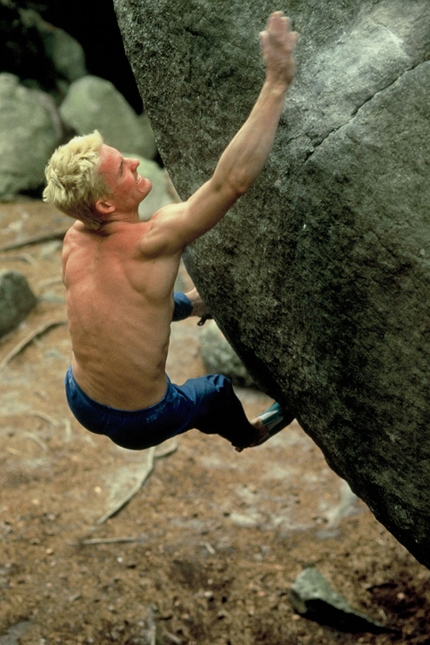

You yourself were really into bouldering for a while, back in the days before crashpads

That’s right, yes! Well I’ve been into bouldering ever since I moved to Sheffield, Jerry was seriously into bouldering and so was I for a while. We never had crashpads at the time. I remember when Marc Le Menestrel came to the UK in the early 1990’s and he walked up to Stanage with what was perhaps a prototype crashpad on his back and we all wondered what it was. That was one of the first crashpads we ever saw, but within two or three years they suddenly became the norm. I wouldn’t dream of going hard bouldering now without one, but back then they didn’t exist so you just got on with it.

Bouldering was a huge part of you life for a while

I gave up sport climbing in 1995 and for the next 10 years was totally focused on bouldering. After my failure to climb my long standing Kilnsey project I lost the motivation to train for sport climbing which seemed very time consuming. I also started up my first business in 1997 called S7 and this took time. I like the freedom associated with bouldering. You need very little equipment, you don’t need a partner and you don’t really need much time to get something hard done. It doesn’t feel as big a commitment as hard sport climbing. I suppose Voyager Low Start means a lot to me because it’s the hardest boulder problem I have climbed and was unrepeated for a long time. It’s also a really cool line which I had spotted many many years before I climbed it. I am also very proud of problems like Cypher at the Slipstones, Eclipse in Little Cottonwood Canyon. It’s the proud lines that you feel most proud of.

Sport climbing and bouldering. What about trad climbing?

Well I still do a bit. I’d just consider myself a climber, I’m into all aspects, sport, boulder, trad, indoor. I love them all, although I am still focused on doing hard sport climbing. I do love bouldering, but it is very intense and hard on the body, particularly outside, where you’re jumping off all the time. Although I can still do that, when you get into your 50's you start to want to look after your body and to get as much out of it for as long as possible, so I don’t really want to do highballs, where I risk jarring my knees or hips.

Makes perfect sense. Concentrating hard on one project makes it difficult to concentrate on other aspects in your life. You have a family, a young daughter, your own company. Juggling all of this is presumably a challenge

It keeps me busy! But the business is going well and after almost 20 years I’ve got a good group of people who I work with and can rely on, which means I have enough time to train and go climbing and look after my family.

Talking about training and business, your Moonboard looks like it’s becoming a standard training tool with many if not most gyms having one!

Well I’ve been doing it since 2006, but things have really taken off since we launched the LED system and the app. The Moonboard came about because we had the Schoolroom in Sheffield where we trained on these very basic holds and boards and that’s when I got the idea of having a board with standardised fixed holds so that anyone could recreate and climb on exactly the same problems. I’d been doing that for about ten years, then a couple of guys got in touch with me separately, Dale Cebula an app developer and Chad Jensen from Alaska who’d developed a LED system and together we developed the LED version of the Moonboard with runs off the app via Bluetooth. Since then it’s gone from strength to strength, but it’s been a long time coming really. I’m really psyched to see people enjoying it.

In some ways it’s ideal for climbing walls because they don’t need to set any problems

Well that’s one of the interesting things, because of how most climbing walls are managed nowadays, problems change every 4 - 6 weeks, so with new problems being set there are never any benchmarks. Whereas on the original 50° board at the Schoolroom, those problems have been there for 20 years. It’s the same with the Moonboard, the problems are there all the time, so you can train and really measure your strength and fitness and see how you’re progressing over time. I also find it’s such a good use of your time. If you’ve only got 40 minutes, with the app you can blast through a load of problems really quick. I personally find it really useful to do a high volume of mid-grade problems, for strength endurance.

Over 30 years ago you also took part in the first international climbing competitions

I did comps starting from 1986 in Bardonecchia in Italy, for about 7 years, mainly lead because bouldering comps didn’t really exist. They were great fun, although I have to admit I always felt a little disappointed, as if I never really achieved what I was capable of. That was probably because I always struggled with the mental side of things. Having said that, I did get a few podiums and finished in the top 10 in the World Cup circuit, so it wasn’t a total disaster I’d say.

How important were competitions back then? In the UK they were quite controversial at first

In the UK, yes, not really elsewhere I wouldn’t say. The first competitions were on cliffs and that obviously wasn’t good because routes were chipped and glued, but competitions very quickly moved indoors and were embraced. Competitions are a great aspect to climbing that add more diversity to the sport. Now it’s a massive, massive part of climbing. And maybe nowadays indoor climbing is even bigger than outdoor climbing! Surely there are more people climbing indoors than outdoors. Certainly the sport climbing crags in the UK aren’t any busier than they were in the '90’s, even though there are way more people climbing.

Did you guys ever think climbing would become an Olympic sport? Was this ever your dream?

I personally didn’t dream of it, but the people organising climbing competitions had dreamt of it for like 30 years, that’s been their really big goal and I’m sure they’re really happy to see it getting in. I think it’s great, if I was younger I’d be super psyched to try and qualify and compete, it’s an amazing opportunity.

Last question Ben: what are you super psyched for now?

Staying healthy and trying to climbing as hard as I possibly can. I really, really want to try and get Northern Lights finished. I thought that was a route that got away from me but after the last couple of years on it I think I might be able to do it, I just need a little bit of luck. We’ll see.

Info: www.moonclimbing.com

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos