New route on Lasunayoc in Peru’s Cordillera Vilcabamba by Nathan Heald, Leo Rasalio

1 / 20

1 / 20 Nathan Heald archive

Nathan Heald archive

For years I desired to climb the peak anchoring the eastern end of the Pumasillo massif in the Cordillera Vilcabamba. Being one of the principal mountains in the area of Choquequirao, it can be seen from the summit of Mount Machu Picchu.

I first caught a glimpse of it through the clouds from Abra San Juan while guiding the Choquequirao – Machu Picchu Trek in December 2012. Since then I visited the area several times and had always been impressed with these large complex peaks. On one occasion in May 2018 I guided a group from Huancacalle to Yanama, hiking over the Choquetecarpo pass. After resting a day in the village we tried to go to the col east of Lasunayoc and have a try on the normal east face route, unfortunately though the group didn’t have the energy for it. But it served as a good reconnaissance and I spied a possible more direct route.

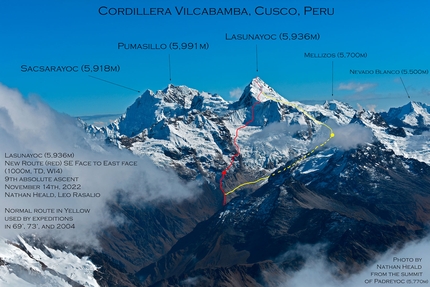

In 2021 my brother Taylor, some friends and I climbed neighbouring Padreyoc (5,771m) and I got a couple photos from high up that gave some good detail of the mountain. I started thinking of trying a more direct route up the south face to get to the upper shoulder, instead of going the normal route to the col and then taking a glacier ramp into the east face. From the photos I could tell there are a couple big seracs that would have to be skirted to one side, but sometimes the way shadows play on the face makes it difficult to see how steep it actually is, in there close to big ice formations. In any case it looked like a wild adventure!

The first ascent of Lasunayoc in 1956 included some members of the first expedition to climb Salkantay in 1952. They approached from the north going up the Rio Sacsara and climbed Lasunayoc by the east face along with a few other peaks to the east.

In 1962 an expedition from New Zealand was based in the village of Yanama for a few months, where they made many first ascents including the difficult Sacsarayoc (5,918m). After trying Sacsarayoc from the ridge connecting it with Pumasillo, a few weeks later they went around the eastern side of Lasunayoc to access the glacial basin to the north. From an advanced camp on that side they climbed the NE face of Sacsarayoc, the NW face of Lasunayoc, and the north face of the unnamed peak between them.

The 3rd ascent was by the Australian team in 1969 that set up a base on the south side of the mountain. They cleaned up a few first ascents of the shorter peaks between Padreyoc and Lasunayoc. They camped just below the col east of Lasunayoc and then circled around to the NE ridge of the mountain to finish to the summit.

In 1973 Ian Harverson and Murray Johns from Australia made what they called the sixth ascent, approaching from the south to the Lasunayoc col, and then trying the NE ridge and eventually finishing on the east face. I believe they counted the 1969 team as 2 ascents since they were a couple days apart. But Im not sure when the 5th ascent was they refer to.

In 1982 a team from the USA approached from the north and climbed several peaks in the area, including Lasunayoc by the normal east face route for the 7th ascent.

It was over twenty years before the summit was made again. Vince Lee led an expedition to climb Lasunayoc in 1988, and got close to the summit by the normal route. (Old School, A Mountain Guide’s Life Before the Net, Copyright 2018, Vincent R. Lee).

The last recorded ascent of Lasunayoc was in June 2004 when a German party of Christoph Nick, Frank Toma, Katja Angerhofer and Christian Klant climbed several peaks in the Vilcabamba range including the normal route of Lasunayoc.

As the 2022 climbing season came to a close, I stopped guiding for a while to work on a chalet my Compadre and I are building close to Ausangate and spend time with my family. October turned to November and it stayed very dry still with many days being totally clear. I really hadn’t climbed anything steep since the beginning of September on Palcaraju, and had been dreaming of getting on some ice and having a long hard day out in the mountains.

For years I have introduced local Peruvians to mountaineering and have cultivated several very good mountaineers. This year my friend Leo got the chance to go on a few climbs and I saw he was ready for something difficult. Leo is an independent tourism guide and has worked professionally as a trekking guide for many years, but had never climbed the big mountains in the area. He grew up on a farm outside of Chinchero and has the natural ability to suffer, weather the elements and keep going with the toughest of them.

We left Urubamba on Friday November 11th and made the long drive to the village of Yanama nestled below these peaks at 3,600m. As we came over the Yanama pass Lasunayoc rose into view in front of us, golden in the afternoon light, too brilliant to note anything about the route. We went to the village and got dinner and a bed and chatted with people hiking to Choquequirao the next day.

A 15 minute drive back towards the Yanama pass brought us to a pasture where we would leave the truck. In 2018 we used mules to move a base camp up next to the moraine of the Lasunayoc glacier, but this time we shouldered our 50lb packs and followed the cow trails that threaded through the tall grass. After a few hours we got on the moraine ridge and followed it to where it disappeared into the peak just south of Lasunayoc, and we found a nice flat outcropping to camp on.

I started setting up camp while Leo went to explore a rock pillar that would hopefully give access to the glacier below the SE face. After a while he came back saying he found an easy way over and we settled in to try and get some rest, but the sun was beating down so much we could not sleep until the sun disappeared behind the mountain at around 5pm.

We woke up at 10pm and slowly got ready, drinking several cups of baby formula with chocolate Nesquik and leaving the tent at 11:45pm. After 40 minutes we got on the glacier and started navigating crevasses in the direction of where the south ridge meets the SE face. Although the moon was bright we couldn’t get an idea for which line would be the safest, huge cornices cast shadows over the wall, so we made it to the corner and started climbing some steep hard ice to get to the ridge. A couple of ropes got us on some airy cornices where I could see and feel the abyss on the other side. Wind came through holes in the ridge and made me certain to stay below the delicate crest, warming up in the light of dawn.

Here we could have kept going on the ridge, but I saw that a traverse under the main serac would get us onto the shoulder faster, so we decided to go for that. Even so it was not easy by any means, requiring a tricky traverse over cornices and then a pitch of steep water ice grade 4 to get up under the serac. A nice catwalk shelf got us out onto a steep slope of loose snow, which eventually levelled off onto the flat upper glacier. Here we took a nice long rest to have a snack, water, and put on our sunglasses and suncream; enjoying the view of Veronica, Salkantay and Humantay rising out of the misty valleys to the east.

The upper mountain seemed deceptively close to us, but after a careful study we realised that the true summit was the peak furthest away from us to the north. We decided to traverse below the upper face and take a more direct line up at the summit instead of trying to follow the ridge which looked OK, but would certainly be full of surprises once we got on it. There was a large Bergschrund cutting across the entire east face, with several weakpoints where we could possibly cross, but you don’t know which will go until you try them. Luckily the place we tried had a way through although a bit tricky, by jumping a crevasse and weaving through a forest of icicles. By this point we were tired and sinking into the deep snow in flat areas, spots where the sun heated it up, the the going got slower. Thankfully there was only one more steep wall of 60-70 degree ice for 70 meters or so and we came out on the summit plateau. A short walk along the broad ridge got us to the highest point at 1:40pm. Although the clouds had come in from the jungle side the weather still held, I could still see Sacsarayoc, the peaks above Yanama and Padreyoc.

Coming off the summit ridge we made a dead-man anchor out of a snow stake and rappelled to the flat area below. We put the ropes in our packs to retrace our way through the forest of icicles, and started plodding back though the glacier sinking in every other step, towards the drop off of the south wall. To get back under the serac Leo belayed me on the steep slope of loose snow, so I could get on the catwalk and put in a couple screws to traverse with some security. As I made the v-thread for our first rap, the light faded and we put on headlamps before descending into blackness. We did 5 rappels; 3 on v-threads and 2 on snow stakes I decided to hammer in to save time instead of looking for solid ice. We were using a 60 meter Mammut 7.5mm Twilight twin climbing rope paired with a 65 meter 6mm Petzl Pur line (static) just for descents, tied together with 2 overhand knots. If you are not careful, as the ropes thread through the belay device the thinner pur line can slip up or “run” a bit. This happened once to Leo and one of the knots passed the anchor cord, making him ascend the length again to pass the knot off the anchor. The final rap took us off an 8m bergschrund to the flatter glacier below, where we stowed the ropes again.

The way out was relatively crevasse free, but its funny how in a mentally exhausted state your mind can play tricks on you and it’s not so easy to remember exactly where you came up twenty hours earlier. Looking for one such passage Leo slipped and almost slid into a crevasse before stopping himself. Meanwhile I still had a half liter of water I was sipping at, but couldn’t hold down any liquid and would throw it up with bile a few minutes after drinking. Finally at the edge of the glacier we struggled to take off our crampons with the straps all frozen together with blobs of ice, but we were out of danger and grateful. We crawled into our tent half an hour later at 1:30am Monday November 14th, twenty-five hours after leaving.

The sun rays woke us the next morning, but we could see the weather was changing and many peaks were gathering clouds, so we descended to the truck quickly. The front tires of the truck had been mysteriously deflated so Leo ran to Yanama to get a pump and fill them up enough to go to the village where there was a compressor. In the end it worked out because there were some hikers coming from Choquequirao who had not gotten a ride out of there for a day and paid me to take them to Santa Teresa.

Lasunayoc does not exceed 6,000m in height, but it is much more difficult than many 6,000ers I have climbed. Even the normal route is not an easy climb and requires navigating a large complex mountain. Leo becomes the first Peruvian to climb Lasunayoc, and many of the difficult peaks of the Vilcabamba like Humantay, Pumasillo, Sacsarayoc, Padreyoc, Panta, etc. have still not had a Peruvian ascent. This climb was exactly what I look for in the mountains: a dream realised after several years, logistical planning, technical climbing, physical fitness, complex route finding, a good partner, epic views and a wild adventure into the unknown!

by Nathan Heald

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos