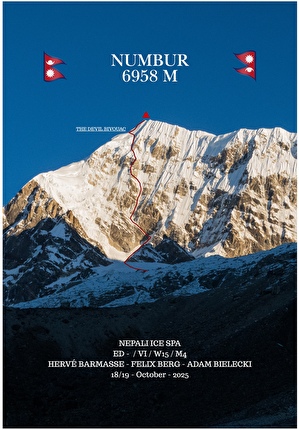

First ascent of Numbur Peak in Nepal by Hervé Barmasse, Felix Berg, Adam Bielecki

1 / 8

1 / 8 Hervé Barmasse

Hervé Barmasse

On the 18th and 19th of October 2025, a strong international team composed of Hervé Barmasse from Italy, Felix Berg from Germany, and Adam Bielecki from Poland made an alpine style ascent of the hitherto unclimbed south face of Numbur (6958m) in Nepal's Rolwaling Valley. The trio initially followed the line attempted by a Catalan team in 2016, via a logical series of spectacular icefalls, before deviating onto a more direct, difficult, and uncertain line that was less exposed to ice and rockfall. One of these rocks hit Barmasse, fortunately without serious consequences. The team also endured an extremely cold bivouac at 6,900 meters, without a tent or sleeping bags, with wind gusts up to 60 km/h and temperatures dropping to -25°C. The route, named "Nepali Ice SPA," has been graded ED-, VI, WI5, M4 and is described as "a thriller of a climb, technically brilliant." Apart from the summit and the first ascent of the south face, what remains however is an experience that tested their resilience and endurance for hours and, above all, a profoundly human journey that might open new doors in the future.

Hervé, congratulations! First off, how are you? How's the arm?

My arm is as good as new. As I wrote on my social media handle, it looked terrible but fortunately the injury wasn't too bad.

So, why this mountain? What's special about it?

We chose Numbur for its elegance. It's a mountain with clean lines, perfect geometry, and captivating aesthetics. There was more though: from the photos, the South Face showed multiple potential lines and an incredibly inviting system of icefalls. For those who love mixed climbing, it's impossible to ask for anything better. Furthermore, in our plans, the ones you make while sitting comfortably at home, or on the plane to Kathmandu, after climbing the South Face we wanted to explore various minor peaks in the area. But as soon as we arrived at base camp and the mountain decided for us. Heavy snowfall during the first couple of days transformed the area from a flowering eden into a winter garden, a stunning but complex environment. It was clear that we'd have to focus all our energy on that single objective. Even the approach to Numbur required hours of trail-breaking through the copious fresh snow.

Let's go back a stage. How did this team come together?

I wanted to return to the Himalayas, but with a different spirit. After the physical and mental commitment required to attempt a first winter ascent of an 8000er in alpine style, I realised I now needed a more technical, fun expedition, and one that would also be useful for future projects on the world's 14 highest peaks. To do that, I needed partners with the same vision. I called Adam - I'd met him years ago, long before he became as famous as he is now talked, shared ideas, and right from the start something clicked. Adam brought in Felix, his long-time climbing partner. That's how this team was born: an Italian, a Pole, and a German. It sounds like the start of a joke, but instead we were a real team. Obviously, along the way we got to know each other better. It's a well-known known that we climbers often have strong characters and personalities. We all feel like leaders, but when the motivation and the goals are the same, the orchestra - the team - doesn't need a conductor. The music plays by itself.

The ascent was complicated even before setting off, with Adam feeling sick at the start.

Adam felt debilitated, he couldn't eat or drink. When we reached the base of the route, he told us that if we wanted, we could continue without him. But a team is a team: you climb up together and you descend together. Any one of us could have been in his place. The strength of a team is remaining united precisely in moments like these. We decided to try anyway, ready to turn back if necessary. I'm sure we would make the same choice again tomorrow. I think you can learn a lot in these situations, too. Mountaineering isn't just about action, it's also about taking time, reflecting.

Initially, you followed the line of the Catalan attempt. Then you opted for a more direct line to avoid ice and rockfall, but even still things didn't get much better and you got hit. From the photos, it looked like pretty bad. Despite that, you continued.

After the first rockfall we realised we had to move towards the rocks on the left, the only area that could offer some protection because it was sheltered below the overhangs. Before we could get there though, there was a second rockfall. I heard Felix shout, I looked up and saw a rock heading straight for me. Instinct made me move a few centimeters and the rock hit my arm, not my head. I felt a sharp pain, but luckily it wasn't broken. At that point, two things decided for us: the desire to continue and the awareness that descending immediately would expose us to even more rockfall. In these situations, you learn to endure pain and deal with it. Once we reached the overhangs we were sheltered from further hazards and the climbing - already brilliant up to that point - became even more exciting. At least until the ice, rock, and hard snow gave way to completely unstable fluff. For the next few hours, zero protection, zero margin: if one of us had slipped... Luckily things went well.

At 6900m you were forced to make an improvised bivouac. I imagine that from the start, you knew this was a possibility? So why no bivy gear?

Honestly, I didn't think we'd need to bivy. Twenty meters from the summit, I turned back and we assessed the situation: fatigue, time, exposure. A bivouac seemed the safest choice. Fortunately, Adam had brought a two-person emergency bivvy bag. A bag you can buy online for 50 euros, nothing super technical, but enough to get us through the night. We found a niche under a snow cornice and "settled in." We didn't panic and, at first, we weren't worried: we thought we'd easily manage the low temperatures. Then the wind picked up though and everything changed. A lot of our good mood (not all of it) and a lot of our energy vanished.

What can you tell us about that night?

The wind turned a tough bivouac into an ordeal. The forecasted temperature was around -25°C, but with gusts around 60 km/h, the wind chill was significantly lower. The charts indicate about -40°/-42°C. The bivvy bag, with no floor, flapped around, the cold penetrated everywhere. Huddled close together, one against the other, we tried to preserve every ounce of heat. It was a night I wouldn't wish on anyone, but also a great lesson on limits and resilience.

Then came dawn, and you set off again for those last few meters that separated you from the sumit.

At dawn, the first rays warmed the air and lightened our spirits a little. Slowly, ever so slowly, we started to move. Some hot tea, a bit of motivation, and then we climbed the last meters. We reached the summit at 10:00 and enjoyed an indescribable view across Nepal. Five minutes of pure joy, then down we went.

How was the descent?

We descended via what we think might be the Japanese route (we didn't find any traces of passage), perhaps with some variations. Essentially down the Southwest Ridge and then on the left side of the south face.

You summed up your ascent as follows: " Technically, one can be ready to climb anything. But for an adventure like this, you are never ready enough." Now that you're back, what do you like least about Numbur?

I wouldn't change anything about what I experienced on that mountain. Numbur gave me much more than I expected and for that reason, there is nothing negative. I don't seek adventure to reach the summit of a particular mountain, to go further or higher, but to get face to face with a part of myself that I don't already know. I'd like to thank Summit Climb for the logistics and especially Adam and Felix. We all know the adage: never trust strangers... and yet this time things turned out perfectly. Who knows, maybe this is only the first chapter.

After the climb you also wrote, "It was a “thriller” ascent, technically splendid, humanly profound. An experience in which, for hours, we tested our resilience and our capacity to endure pain and cold."

Because in certain situations, the mountain places you in front of real decisions. When everything goes smoothly, you don't learn very much. Instead, when you have to adapt, improvise, react... it's in these situations that you grow and understand who you really are. Every unforeseen event moves the finish line a little further away, but also enriches the experience. Numbur tested us in every possible way: technique, mental clarity, mutual trust. New challenges await me, but in order to face them I need to know exactly how much I'm willing to give. Numbur made me understand that. The fire inside me is still burning and I have many ideas for the future.

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos