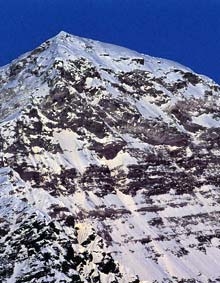

Davo Karnicar, skiing down The Ultimate Ride on Everest

1 / 4

1 / 4 arch. Davo Karnicar (Elan)

arch. Davo Karnicar (Elan)

Everest is by far the highest mountain in the world. The Earth Goddess of all mountains. The inspiration for all those who have stood on her summit. In our freerider soul it is the supreme descent, the ultimate ride. Davo Karnikar became the first person to carry out the complete ski descent of Everest. The 38-year-old Slovenian talks to us about his skiing adventure.

So Dave, where did the idea to ski off the roof of the world come from?

My brother and I spend most of our lives travelling following the World Cup circuit, working as technicians and ski men for Elan. Up until a short while ago I worked for Furhuset, but I always managed to go away on expeditions overseas – about one every two years, to ski down the highest mountains in the world.

In 1989 I went to Narga Parbat for the Diamir face, in 93 I went to K2, in 95 I went to Annapurna where I reached the summit and made the first ever ski descent. It was there that I realised I’d be capable of skiing down Everest and the idea soon began to transform into an obsession. In the meantime I summited another 8000m peak, Shishsapangma in 1996.

Your first attempt at Everest?

In ‘96 I tried to reach the summit from the north, but at 8300m I was forced to turn back. Even if this was a big disappointment that extenuated my obsession, it proved to be a great help to discover what I really needed to successfully reach the summit.

During my first attempt I lost two fingers due to frostbite – my index and little finger. I realised then that I’d need a team of people to back me up, specially designed gear and, above all, I would try from the other side, from the south.

Just like Kammerlander I encountered very little snow. Even if I had reached the summit I wouldn’t have been able to make a continuous descent. I don’t reckon one can make a continuous descent down the N. Face: the colouirs are difficult and very rarely in condition (Editors note – this interview took place before Marco Siffredi’s snowboard descent).

So you chose the South Face. Obviously not the cheapest of options.

No, absolutely not. The costs are staggering: $70,000 just for the permit. I tried to raise the money for two years but failed. Then I considered diversifying the project, making it innovative. One of the staff members came up with idea of transmitting the entire expedition live on the internet, day by day, hour by hour.

It soon became clear that this was the only feasible option, even if the costs doubled! But, incredibly, it proved easy to raise the necessary funds thanks to internet, much more so than a cheaper project with traditional sponsors. If I’ve stood on the summit of Everest with my skis, then its only thanks to Internet.

So you found yourself caught up in a huge communications project, totally different from what you were used to. Was it difficult dealing with your staff and your emotions? Did you feel under pressure?

It wasn’t easy managing such a big and diverse group of people. There were 6 mountaineers in the group, but also operators, telephone technicians and journalists. It wasn’t always easy, but I knew that it was my only and probably last chance to ski from the top of Everest, so I made a huge effort to make the most of the situation.

I knew that I had the eyes of Slovenia watching me; Simodil (the national Telecoms operator) had put a lot into this project, but my attention was entirely focussed on the mountain and on my descent. That’s what I was there for, the others had to take care of everything else. My task was to manage the mountaineers assisting me as best as I could, and to try to gratify each one, but not to lose sight of my personal goal. At times I had to assert myself over my companions. You know, Everest is a huge temptation for everybody.

How did things go on the mountain?

As with all normal expeditions to Everest, first we had to acclimatise, then carry up the gear and equip our camps. Then we had to wait for good weather for our summit attempt.

It took a huge amount of effort, because climbing in autumn with no other expeditions around meant taking on a huge workload. Each time it snowed there was no one else to beat the trail. I reached the summit during the night of 7 October, and at 8 o’clock the next morning I was ready to ski down.

Did you use oxygen?

Yes, my main aim was a complete descent on skis, so getting to the top was just the start of my adventure. I couldn’t risk failing to get to the departure point. In autumn the temperatures are very low and without oxygen you feel too cold. It’s a compromise I had to make.

Now it’s over, don’t you regret having used oxygen? Don’t you feel as if something’s missing?

I made a step forward with this kind of adventure. In a few years someone will probably make the first complete descent without oxygen. Let’s hope so. Mine was just a step, there are a lot more to take. In any case, the first complete descent from the summit of Everest will always be mine.

Where are the most difficult sections on the South Face? The Hillary Step just below the summit creates problems for mountaineers. How did you manage to ski down it?

Skiing down the Hillary Step proved to be a lot less difficult than the previous section, along the very thin and exposed crest. It’s delicate and you really feel the altitude. You can probably deal with it better on a snowboard. On skis it’s complicated because there isn’t much space.

I got round the Hillary Step by skiing to the left, down a kind of exposed gully. From there to the South Summit the descent is very technical, and from here I continued without oxygen. The next part is pretty delicate as there’s a risk of avalanches. I didn’t exactly feel comfortable skiing on those wind slabs!

Then from the South Col, how did things go? Did you stop?

Yes, I stopped for a drink and to put the digital camera on my helmet. It was quite a short stop. At 11.30 in the morning I reached Camp One, at 6000 metres, just above the Ice Fall.

How did you manage to get past the Ice Fall without taking your skis off?

There’s only one way to avoid the Ice Fall. I had to keep a diagonal line high to the right, immediately beneath the South Face. It’s exactly the kind of place you’d never want to be in: steep and exposed to the serac falls from above. What’s more if you fall you’d certainly finish off right in the middle of the Ice Fall - they wouldn’t even get you out in little pieces.

I was extremely tense and tired. Then at last, at 12.40 I got down to Base Camp, glad that it was all over. I’d been on the go for 15 hours, I felt drained and couldn’t sleep. It was as if I was light years from this world. I couldn’t even manage to feel happy.

Now how do you feel when you think about “your” descent?

I

feel a huge sense of joy. You’re right to stress the word “your”. I feel that it’s something that is absolutely, intimately “mine”. Deep down I’d always thought that I had a date with destiny on that mountain. I was sure that sooner or later my dream would come true. I had to sacrifice several things for this dream. Even my four children have been caught up in one way or another in this adventure that has been accompanying me right through my life as a skier. Even their lives have been touched by Everest. The mountains have often kept me away.

Other projects?

Now I’m totally satisfied, I haven’t got any future projects. I can’t manage to find any, everything seems so far away after that descent. I’m surprised at how weak my desire to find another goal is. Maybe I’m too satisfied with my life at the moment and the fact that I’m not a professional means I can be free, that I’m not obliged to invent something even more difficult. Right now I only want to take my children skiing and climbing.

Copia link

Copia link