New climb on Corno Grande del Gran Sasso (Italy) by Fay Manners, Marco Malcangi

1 / 13

1 / 13 Fay Manners archive

Fay Manners archive

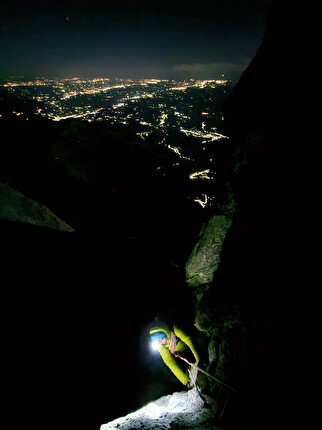

On Thursday 4th September, we drove to Prati di Tivo in Abruzzo, a quiet mountain village nestled beneath the rugged limestone peaks of the Gran Sasso range. Only 150km from the capital, the massif feels like a different world. I had read about the area’s potential for steep skiing over the past year, but more recently, my focus had shifted to its climbing, particularly the striking faces around Corno Grande, the highest peak in the Apennines.

Looking through old guidebooks and alpine maps, I was intrigued by the variety of terrain: pocketed limestone slabs, wild ridges, alpine gullies, and historical via ferrata routes. Among these, Paretone and the east face of Corno Grande stood out as major alpine objectives, reminiscent in character (though not scale) to the Dolomites.

Marco had a week off, and I was just coming back from a 7-week ankle injury - not fully healed, but healed enough to chase an adventure. We both had the same idea: explore an area we’d dreamed about but never visited.

We hiked up to Rifugio Carlo Franchetti and spent the afternoon exploring the mountains with binoculars, scouting the faces for possible lines. The north-facing Jannetta couloir - a line we both dream of skiing in winter caught our eye, but we were drawn most to the face of Corno Grande’s Eastern Summit (Vetta Orientale), especially to a series of buttresses on Pilastro IV.

Despite the mountain's popularity, we spotted what looked to be an unclimbed line: a clean, direct corner system rising up the central part of the buttress. The access looked a little complex, steep and broken but the line itself was clear. Aesthetically, it was obvious. We checked the guidebooks and spoke to locals, and as far as we could confirm, it hadn’t been climbed.

We left the hut early the next morning, carefully selecting gear. Climbing in the Gran Sasso carries a strong ethic of minimal bolting and alpine style. Most routes use a mix of traditional protection, pitons, and sparse bolts where absolutely necessary. As a Brit, this style resonates deeply with me, and I was ready to leave the drill behind. However, after inspecting the face, I made the decision to bring it; not to make the climb easier, but to ensure the line would be safely repeatable.

In total, we left five bolts on our 200m line. One on the first pitch to prevent a ground fall and mark the start of the route. A second to protect an unprotectable traverse section avoiding a wet and loose roof. Two for the anchor at the top of P1, where natural placements were unreliable. And one high on the final pitch to protect a loose and dangerous chimney section.

All other protection was traditional - a mix of cams, nuts, and threads. We used natural gear for belays wherever possible, including almost all the anchors.

The first 4 pitches were of high quality, with well protected cracks but with bold and technical moves inbetween. Our venture to climb this line was worth the effort as pitch number 4 was best pitch; long and relatively clean with beautiful movement up a steepening corner.

The upper section of the mountain quickly revealed its true nature: loose and unreliable. This confirmed what many had warned us about, and it’s exactly why we chose the name Eppure Siamo Andati — “And Yet We Went.” Despite all the advice, we ignored it and pushed on. At first, we had hoped to continue our new line all the way up, but when we arrived on the upper face it was clear that every option was dangerously unstable. The historic Mario - Caruso ridge offered the most logical and slightly safer exit, so we followed it to the summit.

We topped out beneath a full moon, exhausted but satisfied. The final meters took longer than expected, weighed down by heavy packs and the fatigue of the day. Just after midnight, we arrived back at Rifugio Carlo Franchetti tired, sore, but carrying the quiet contentment of having carved a bold new line on Corno Grande.

- Fay Manners, Chamonix

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos