New Greenland climbs by Ben Kent & Robbie Milne

1 / 23

1 / 23 Ben Kent archive

Ben Kent archive

"Good luck with future exploits! Just don’t count on them going as smoothly as this one!" - We mulled over this, somewhat amused as we touched down in the small village of Maniitsoq. It was a comment left me on a short piece I wrote on the last new routing trip to Greenland in 2024. Now almost exactly one year to the day that we had arrived by boat in the West Greenland village we had just flown back for another taste of wild landscapes and miles upon miles of untouched granite.

The last trip had taken weeks of sailing to reach Maniitsoq. The trip this year, although much more streamlined had still not been all that straightforward. Three boring days grounded by fog in the rather bleak capital of Nuuk had left us itching to get stuck in. Although that being said, it had provided us with the chance of a shower and a hot meal in a hotel paid for by the airline. A point both me and my expedition partner Robbie Milne had agreed was a big win as we had spent the previous two days bivvying in the gravel with our haul bags waiting for our connections. Every cloud…

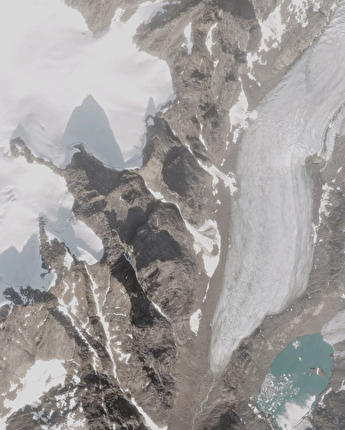

This year we were swapping easy access coastal walls for big alpine peaks and glaciated terrain. More kit, more faff, more suffering surely equated to more fun? Our small unlikely team consisted of myself; a 26 year old climber from the English Lake District and Robbie Milne; a 22 year old ski instructor from France. Our destination was a blurry screenshot of an intimidating looking ‘shadow’ of a peak at the end of a huge glacial lake from google maps… Not much to go on.. but it looked like a potentially spicy objective.

The intel besides the glimpses of views in the distance from the previous trip consisted of 3 photos taken by a German couple who had trekked through the fjord 10 years previously and a report from one of the very few teams to have visited the area. A British Army expedition from 1967 where they had done some mountaineering in the surrounding area. Whilst they had not been there to climb big walls a few of their words describing one of their more adventurous outings had sparked imagination. One sentence in particular: "The second had the rock experts talking about it for days afterwards: 1500 ft. of diedre capped by a cottage-sized chockstone, enormous boiler plates of slab and pitches of V nearly all the way to the final summit ridge."

Our real secret weapon was our friend Salik. A proper local, trawler-man and general lad about town. Maniitsoq born and bred, he knew the fjords better than you know the aisles in your local shop. Everywhere you went he would tell stories of who owned each small island, who likes to fish here and tales passed down by his Father. Not only did he have a boat, something essential for travel in Greenland, but also a canoe that he had kindly agreed to lend us for the expedition. We had spent a week last year helping him and his girlfriend build a lodge on the coast which he hoped to set up as a tourism business one day. Trawling is a young man's game he says. Greenland is one of those places you spend a few days with someone you meet by pure chance and end up knowing them for the rest of your life.

Salik met us on the runway after a short 30 minute hop from Nuuk on a cold and clear day at the end of June. We had a small wait for our bags, not because of the traffic; there were only six people on our flight. But more because of the fact that every member of staff, passenger and even the pilot had to say hello to Salik before any work could be done. Small town, big characters.

A quick food shop in the local ‘Pissifik’, the customary visit to the local hardware store for Salik and we were ready to go. We had dehydrated most of our main meals and brought them with us but the necessities like chocolate, tins of mackerel and porridge oats we were buying in Greenland. The age-old question of more food, more carrying, or less food and rumbling stomachs was in the air a lot. The 45km trip up the fjord to the head of the lake would take just over an hour and a half at Salik's breakneck sailing pace. Not really a hardship when the scenery was like that of a documentary you might watch on tv and whales were breaching every 400 meters. About halfway we made a quick pitstop to grab the canoe. ‘Grab’ being Greenland style of a quick 20 minutes walk uphill across boulders to the head of a lake where it had been stashed then a rather more than 20 minutes mission back to the sea with it balanced on our heads.

Salik dropped us at the head of Ikamiut fjord with a promise that he would be there in three weeks time as long as ‘the wind wasn’t too bad’ and sailed off into the evening. Weather was good, we had a lake to cross, a basecamp to build and he had roofing to be done. In Greenland they say they have two seasons. Winter season and building season. His parting note in true Salik fashion was "oh by the way, I’m not too sure if the lake you plan to paddle up is still frozen."

The first trip up the portage was a somewhat worrying one but mercifully the lake had thawed and we soon got about carrying the 120 or so kilograms of food and equipment we had up to the lake. The views were pretty special. Not often you carry a canoe whilst watching enormous hanging seracs crack and avalanche down a mile high face.

We were without a breath of wind for the paddle. A fact that we both voiced was an enormous stroke of luck considering our overloaded canoe and a freezing lake that was supplied straight from a hanging glacier on its southern shore. We were without lifejackets or any form of extra buoyancy in the the canoe so chance of survival following a capsize on our 4km paddle would probably not have been in the higher end of probability. Although we had originally planned to keep as close to the shore as possible, the downdraft off the glaciers above quickly pushed us out over half a mile into the centre. The wild remoteness of our situation was starting to sink in. No disasters here lads, because nobody is coming to get you.

Basecamp at least, was obvious. The only flat area for miles was a large tongue of old moraine, eroded over years to a sandy floor carpeted with moss and Dwarf Willow. Flat as a pancake and quick draining. Suddenly the decision to go heavy on the food all made sense as we pitched our tents 10 meters from the canoe. Result!

The time was 8pm by the time we had finished setting up camp and had made a quick meal. Perhaps it was the arrogance of youth, the adrenaline of being in the mountains after months of planning or a combination of both but the early 6 am wakeup for the flight in Nuuk had quickly been forgotten.

We knew from Salik’s weather forecast that we had another 24 hours of good weather before a storm rolled through so surely a quick scouting mission to go scope out our peak couldn’t hurt. In the big mountains weather turns fast and from experience when a weather window is there you should usually take advantage of it.

It was soon decided that a quick and fast alpine approach would be best, a slimmed down rack, 1 axe each, a packet of apricots, 2 tins of fish, some cheese and some rye bread. From screenshots of google maps we knew the peak should lie around 3km up the valley. We had found satellite imagery invaluable in planning, it was a much welcome perk of the now modern world of alpinism. Although accurate close to the coast, the mapping in the interior, especially in unclimbed areas was void of much detail. Without it we would have been largely in the dark about what we might have encountered.

Around an hour of an ever unhelpful uphill struggle through the moraine later we reached the much more solid glacier and soon made quick progress to the base of a huge broken and chossy wall. On its right was the access gully which we believed to lead to the peak. From our scrutiny of the satellite maps we had hoped to climb the east face to the summit but it was quickly obvious that this wasn’t going to go. It looked wet, steep and very intimidating. It was only June and although the sun was in the sky for 24hrs much of the upper slabs were still snow covered. The air temperature was only a little over freezing. Thankfully a steep snow filled gully capped by some huge chockstones looked like it might be passable. By this we hoped to reach a col where the north ridge looked like it might be climbed fairly amenably.

The air has incredible clarity in Greenland. There is little in the way of landmarks by which you might judge size or distance and so it is always very hard to grasp scale. We knew the hight of the summit from a contour spot height given to us by our in- reach but there was no way of knowing just how long the gully might be. Invariably 500m of elevation front pointing up steep névé up what we thought was going to be a ‘quick bash to the col’ left us at the chockstone more tired than we wanted to be but still in good spirits. The time was now midnight.

I racked up ready for a bit of a fight with the chockstone but it passed easily at about M4/5 and gave way to a chossy final few hundred meters up the gully. We reached the col at 1:30 am and the view we were presented by was pretty special. Bathed in alpen-glow from the midnight sun the huge hanging glaciers were truly spectacular. The righthand side of the ridge looked doable, clearly the less hours of sun on the north west face had made all the difference in this early season and reduced the melt. Maybe the summit was on!

We wolfed down a couple of apricots and changed into our rock shoes, it was going to be a long night… I can’t remember much of the following pitches. Not because they were boring but because I was in such a state of exhaustion by the top that they began to blur into one. I'm fairly sure the climbing was fantastic though. Ridiculous exposure and manageably dry in between some wet streaks with difficulties averaging around E1- E2. We hugged a solid band of rock that split the North Ridge and the North West Face. On one side; granite slabs and corner systems as far as you could see and on the other a straight 700m drop to the glacier below. It was bitterly cold though, we were now well over 1000m above sea level at 3 am and the air temperature was below freezing. Many of the cracks were blocked with ice and numb fingers and toes had to be accepted. I was the faster leader and so with the interest of a closing weather window and a summit to be had, I block led the face while Robbie took all the jackets and our small rucksack.

Nine pitches later I was knackered. It was 8 am and I could see one final mixed snow and rock pitch before what we hoped was the summit. It looked pretty hard and I spent a while searching in vain for a way through. I shouted down to Robbie to let him know the situation, but there was no answer. I shouted again. I have on Robbies account that at this point he woke up whilst belaying. We were now well into our 26th hour of being awake.

I brought Robbie up the stance and after some discussion I decided to make the final push with some ‘bomber’ skyhooks as protection across a blank slab, then knee-deep in rock shoes with completely numb toes across a short snowfield which guarded the final wall. After the bold slab a final steep and safe crack to the summit ledge felt like a gift and we topped out at 08:52 am, 1600m of ascent later and 13 hours after leaving the tents. The views were astonishing but there was little time for jubilation sadly. As all alpinists will tell you with a twinkle in their eye, the summit is only halfway. The north wind that brought the stable weather was turning. Clouds were starting to form to the south and the weather window was closing.

I'm unsure sure how we managed to scrape through 800m of abseiling without any major mishap but we did. Robbie was invaluable, flying back up a quick 15m pitch to retrieve a stuck rope and spotting some great threads by which we could abseil off minimal lengths of cord. We left nothing but 2 nuts and some cordelette on the face. After cursing the length of the snow gully on the way in, we rejoiced when we finally reached it again. A gift for our knees and relative safety. We reached the glacier and stumbled the final few miles back the to the tents like zombies. Everywhere we could both hear voices in the rocks and streams. After a quick demolishing of some pesto pasta we collapsed into our sleeping bags exhausted but happy. Awake for over 36 hours we had completed the expedition objective on the first night…

After our first successful yet rather full on encounter with the mountains a 2-day period of rain and low cloud was welcomed. A great excuse to lie in bed, rest and eat as much as we could without depleting our stores too much. A benefit of taking so long climbing the first route without hot meals is we could now eat four days worth of rations in just two! Get on! Much sleeping and forecast checking later the sun returned. Another 48-hour window was on the horizon and the suffering of two days previous was soon forgotten. Surely it was high time for another adventure.

The objective for the next big route was another alluring face at the head end of the same valley. Every morning the sun bathed the huge granite slabs on its east facing flank with a golden light. It was the obvious choice.

This time we had learnt from our previous sleepless outing and opted to bivvy at the base of the face ready for an early start the following morning. A relaxed walk back up the glacier with heavy packs to the base of the face took us most of the afternoon. We had brought a shovel up with us to dig out snow for a bivvy so flat ground was not a problem and we soon had a pretty cosy shelter underneath a nicely overhanging boulder. The face was still shrouded in thick cloud however and it had started to rain again. It was pretty obvious that the line we had hoped to do would be wet but we went to sleep anyway with the hope that when the cloud lifted we might be able to see a line.

By 3 am the cloud had lifted and after a quick breakfast of lentil dahl and mackerel we set off up the corner systems at the righthand side of the face. From a binocular inspection it looked both the driest and the most amenable climbing and perhaps not as long as the original planned line on the lefthand side. Again, Greenland's air clarity and perspective of standing below a very tall face was playing with our minds.

The climbing soon became very absorbing with a somewhat serious nature. Steep cracks and flared grooves on scrittely rock and booming flakes. 2 pitches in and Robbie quite wisely decided that it would probably be best for me to stay on the lead. Although a strong climber, he was used to following nice shiny bolts in the Alps and the questing nature of the climbing combined with a lot of gear trickery was definitely on the more demanding end of the scale. Clearly a lifetime of fiddling wires into mossy cracks in the Lakes had prepared me well. Whilst not technically hard (maybe only around French 6b) the exposure and nature of the rock really made you feel like any falls or dislodging of flakes could end up being extremely serious.

As is fast becoming a theme with mine and Robbie's days out, it soon began to dawn on us that the face, whilst looking small, was in fact flippin massive. 11 tough pitches later we lay on a ledge for some respite. Whilst bringing Robbie up the previous pitch to the belay both my arms had started to cramp so severely I'd had to tie him off and lie down for a few minutes. I'd been on the lead well over 14 hours and was in need of a rest. We had been in the shade most of the afternoon and so we took an hour to apply all available jackets and admire our position whilst snacking on some well-earned salami and cheese. Mercifully after another steep pitch the angle was finally beginning to ease. We had made it into a huge drainage groove that looked like it led all the way to the summit. Agreeing that a well-earned tin of Mackerel in the sunset was now well within reach we pushed on with renewed enthusiasm.

We could see however that a final headwall really kicked back steeply. It's always a bit worrying on first ascents of this scale that you might get 50m from the top and find a huge blank overhanging wall stopping you right in your tracks. We had no hammer or bolts, so if there was no features that would be it. Thankfully no such bastard blank bulges arrived and I found myself pulling over onto one of the most insane views I think I will ever see. Endless nameless peaks and glaciers stretching away towards the coast. Even Robbie agreed it was maybe better than any French view he had seen, which is rather big praise from a Frenchman. Not a bad spot for a nice 10 pm lunch at any rate.

Once again abseils loomed before us. Two ropes stuck this time and a cold 6-hour descent, yet there was only one major sense of humour failure during a repeat of one particularly unpleasant 50m pitch to unwedge one of the lines from behind a flake. 24 hours after leaving the bivvy we glissaded back to it, picked up our stuff and began the now all too familiar route down the glacier. Another successful mission.

The next week and a half was marred by bad weather. A large storm persisted for nearly 6 days and brought the snow level all the way down to camp which put a hold on our rock objectives. When it finally abated everything was looking rather wintery and our canoe which we had weighed down with rocks was now full to the brim with rainwater…

In a rare ‘short’ day for me and Robbie we made an alpine style smash-and-grab hit on the inspiring peak overlooking our camp. Robbie was in his element on this one and put in a pretty impressive effort of kicking the steps up steep snow and ice for 1700m of ascent in a matter of a few hours. This was our only non ‘first-ascent’, as the 1967 team had claimed this as their biggest prize of the trip (being the tallest summit in the area around the lake). Certainly worthy of such praise we agreed as we admired the view from the top.

The fourth and final route of the trip came just 48 hours before pickup. The weather window we had been watching on the In-reach had been creeping ever backwards and we were worried that we might miss it. Salik would be picking us up on the 16th of July. With more high winds of over 50mph forecasted for the following days there was no room for being late. Wind on that scale would make both Salik's journey and our paddle back up the lake simply too dangerous and we did not have the food stores to sit it out.

We decided to commit for two reasons. Firstly, the lefthand side of the spire we had originally hoped to try before being shut down by wet rock was playing at the back of our minds. The ever-present ‘what a line it would be if we did manage to get up it’. It would certainly be the biggest, most direct and potentially hardest route of the trip. Perhaps a perfect finish to an already successful mission. Secondly, I had left my favourite chalk bag at the top of the other route when I took it off to go to the toilet! I was dammed if I was going to leave the faithful bag to a life of solitude next to a turd for all of eternity. The chance of it still being there after snow, raging winds and torrential rain was slim, but not zero.

To give ourselves the best chance of success we spent the last drizzly day walking the 4 miles or so up to the base. We were going to haul this time. The route looked hard and I didn’t think I would be able to lead it all alone without a good rest somewhere. More weight and faff certainly. But a sleeping bag each, more food, some pitons and large cams sounded like a good recipe for topping out without too much of an epic. That night we returned to the tents for a big feed and a good sleep. The next day dawned clear. Perfect weather. We positively bounced up the glacier, this time without rucksacks on. The route looked dry and forecast was holding. It was on.

This route was certainly what we had hoped for. Perfect rock, sustained steep pitches up to around E3 and a direct line for hauling. The route-finding was hard though. Although the cracks were often vertical, they often split into two or three potential lines. Many a time we found ourselves at a belay squinting up and looking back on photos we had taken at the base to try and work out which crack kept going and which blanked out. Again and again we chose correctly, and after some incredibly unlikely moves across a perfect slab we made it to a halfway ledge we had spied from our old bivvy site. This ledge was far from palatial but it would do. Nine pitches down. It was time for a rest. Temps were well below freezing again as the sun had crept westward and out of reach. We huddled together in our bags expecting a long and uncomfortable 3-hour wait for the sun to come back round, but to our surprise we woke up hanging in our harnesses to the sun. Result! We hadn’t even remembered going to sleep!

We couldn’t have had more than an hour or so in an incredibly uncomfortable sitting position whilst pressed against the wall, but we felt like men renewed. We wolfed down some chocolate and apricots and pressed on. Superb pitch after superb pitch came and went including a memorable 20m climb then 5m traverse and a 20m downclimb back to a ledge and corner system, just out of reach from our starting point. Here we fixed one of our lead ropes and zip lined the haul bag horizontally, much to our amusement. Robbie also got his first lead of the trip following this pitch. A mandatory E2 5c crack downclimb 600m above the glacier. Not bad for a skier!

The last pitch sadly did not go free. An overhung corner crack which was completely sopping. It went easily at A1 but if anything we felt like it added to the adventure. We topped out victorious onto a perfectly flat ledge almost exactly 24 hours after setting off. Sleeping bags were out in a flash and we had a wonderful few hours of sleep in the afternoon sun. The routes were definitely starting to take a toll on us and our ability to recover was noticeably worse than on our first few outings. We were very glad we had made the decision to take the extra gear this time but we weren’t quite done yet. Another 3-400m of scrambling over a wild looking summit ridge would hopefully bring us back to our abseil line which we had carefully noted from our previous route.

As we simul’ed along the ridge the trepidation began to grow. It was easy terrain and we flew along it in less than an hour. Again the clouds were coming in, much of the base of the wall was now shrouded and the temperature was dropping again. However with the bonus of our memorised abseils we weren’t too worried. We had trundled a huge amount of potentially dangerous and rope snagging rock on our first trip down the wall and so this time it should be much safer. Robbie began to quickly set up the first ab whilst I nipped around the corner of the huge summit block. There it was! My Aiguille chalk bag, given to me by my best mate Chris. Full of water, but still valiantly sitting proud atop the boulders. Clearly the route was meant to be!

Between the dates of 28th June - 16th July 2025 the team climbed:

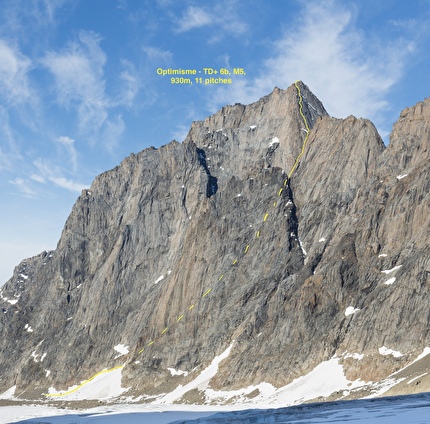

- Optimisme - TD+ 6b (French), M5, 930m, 11 pitches. GPS: - 65.818010, -52.584283

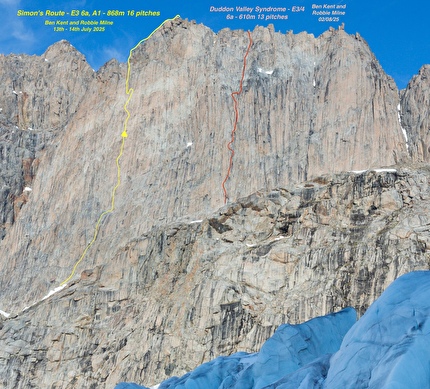

- Duddon Valley Syndrome - E3/4 6a, 610m, 13 pitches. GPS: -65.832862, -52.562846

- Simon’s Route - E3 6a / A1, 868m, 16 pitches. GPS: -65.832862, -52.562846

The summits themselves we left unnamed. These mountains certainly don’t belong to us in a wild place like this. We simply feel privileged to have been able to have adventures on them and escape unscathed without them noticing.

- Ben Kent, Lake District, England

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos