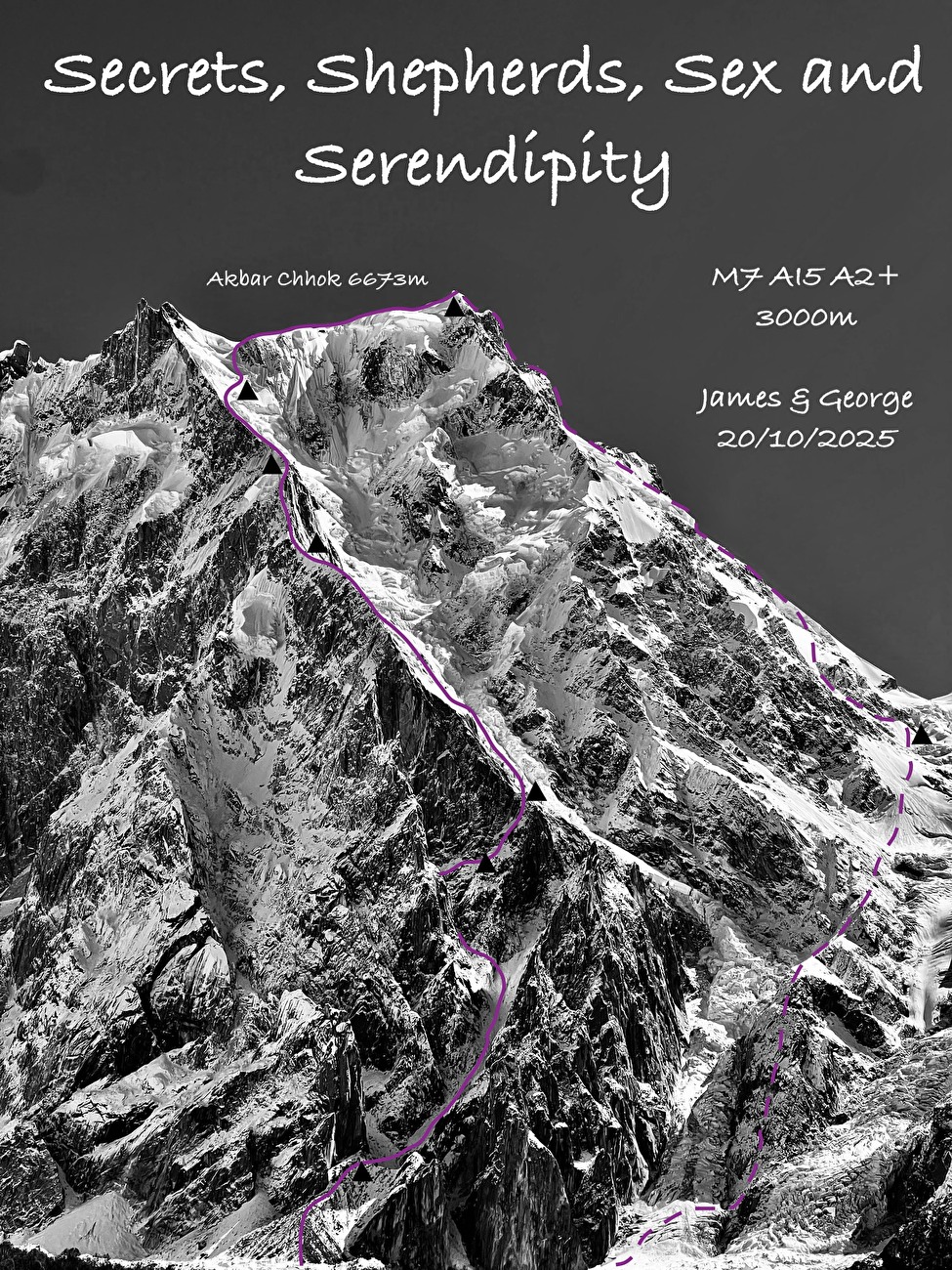

First ascent of Akbar Chhok in Pakistan by George Ponsonby, James Price

1 / 29

1 / 29 YAG archive

YAG archive

We had spent a week and a half in basecamp riding out bad weather, checking out lines to climb and hanging out with the other members of the YAG, with the local climbers Hassan, Adnan and Najeed, and with the shepherds who had kindly lent us a hut. After wandering all over two valleys, making our way up to Sani Pakush on one side and Batura base camp on the other side, we settled on a line we could see through the door of our tent, up a ridge/buttress straight up the northwest face of an unclimbed peak in the Haachindar Massif.

Finally, a massive weather window arrived in the forecast, and all three teams at base camp started to prepare for their different climbs. Anticipating around five to seven days for the climb, we packed five days of food and seven days of gas, while the shepherds hung around staring at our gear, chatting and every so often exclaiming that the mountain was ‘very dangerous’. A local imam had arrived a couple of days before, and told us that one glacier beside our route, while normally a no-go zone due to the seracs above it, would allow us safe passage the next day. Despite this prediction with the weight a holy man’s word behind it, we still decided to go a different way. Very little shepherding was done that day due to the distraction we provided, and it all got a bit much by the end, so we retreated to the hut for 30 minutes before leaving. James stuck in some earphones, I zoned out, and Akbar, the head shepherd who’s hut we were using, came in and made us chai while singing softly. With that send off, it felt like the stars were aligning for the route, and we had to get up it. That evening we crossed the glacier and bivvied at the base of the route. Both of our bags broke on the approach where the shoulder straps and waist straps were connected, so I cooked that evening while James repaired the bags with our suture kit.

The first day of climbing started out strong, making good progress up a main gully, then left into a side gully, before reaching about 6 pitches of mixed climbing up to M5/M6 to connect small snowfields further and further up a face to try and reach the ridgeline. One memorable pitch involved the leader needing to be lowered into a small mixed/thin ice couloir, with the second needing to make a tensioned jump into it. The day ended three pitches below the ridgeline, both of us happy about the progress and naively thinking our five-day timeline seemed pretty reasonable.

Day two then kicked us right up the hole. It took all day to climb three pitches of mixed and aid at around M7/A2+. James put in a very good effort on pitch two in particular, which involved a slightly overhanging aid crack on rock that got looser and looser. I finished off the climbing on a pitch that started out as steep mixed, leading to slabbier mixed buried in powder that finally led to the ridge. Exhausted, we moved to the south side of the ridge and set up camp in the first bit of sunlight we had seen in a couple of days. Even though we were on the south side of the massif, we were on the north side of the mountain, and the ambiance had become a little too ‘Grandes Jorassess-ey’ for our liking. Seeing the sun felt like quite the blessing.

On day three we actually managed to get everything inside our bags – no more jackets or water bottles swinging around attached to the outside. We left the ridge for a bit, due to steep, compact rock we were unable to climb without rockshoes, and moved up a steep, broken glacier and snow ledges, before moving back up to the ridge on easier mixed ground, reaching a bivy site before what we had dubbed the ‘second rock step’

Day four required navigating the second rock step, with the only possible option being to climb it via ice slopes on the north side. After abseiling into the ice slopes and climbing a few traverse pitches, we climbed into a dead end – I had hoped to climb up to the ridge, where we could move across easy ground for a bit back to the upper ice pitches, hopefully eliminating three or four pitches of ice along the way. A few hours into a half ice, half mixed pitch, it was obvious we weren’t going to make it. With daylight fading, a retreat was made back to the bivy to try again the next day. That night, to make ourselves feel better, we made what we thought was custard, but ended up being some uneatable, mango tasting, plastic-like substance that had to be thrown away. We decided to change up our tactics, and as I had more experience on ice, I got a light leader bag, 6 screws per pitch and a brief to get us through the ice as fast as possible.

Day five got grim. It was a long, long day of ice climbing with 8 pitches up to AI5, most of them 60m rope stretchers on rock solid glacial ice, and a vertical snow pitch to exit back to the ridge in the dark. After four pitches of bashing our way up, mistakes started to be made due to the fatigue and battered toes/hands. Despite most of the ice being relatively easy on a normal day, the building exhausting led to sloppy placements and a couple of unhappy moments like both feet blowing. An unprotectable snow pitch was the cherry on top. The feeling of relief when we both topped out the second rock step at 5700m in the dark was immense. Casualties included two partially broken ice screws and a chipped pick.

Day six we prayed for a nice, easy snow ridge to the mini summit. I could have cried when we packed up our bivy, moved over a small hump and saw nearly 1000m of black ice up the ridge, with some chossy rock steps thrown in. Both of our feet were absolutely battered from the day before, and this looked like it was only going to compound the battering. This was the day we perfected what we dubbed the ‘Karakorum flop’. To execute a good flop, you climb as far as you can up slabby black ice from your last ice screw, ideally while simul-climbing. When you can’t take the pain in your toes and calves any more, you drive in the ice axe and clip straight into it. Then, relax every muscle in your body – if the bag starts to tip you backwards, just let it, don’t fight anything. After a minute of complete relaxation, only then do you start to even think about putting in a screw. Clip the screw, then rinse and repeat the entire procedure until you’re out of screws. In the evening, with no good bivy spots in sight, we traversed to the glacier on the right and found a bivy spot in a crevasse at 6150m, again after dark.

Day seven continued up the glacial face with more some snow simul-climbing, an overhanging ice step and one and a half pitches of steep black ice to the ridge between the mini-summit and the main summit. My block ended once we reached the ridge, and as I was belaying, the sun finally appeared. Having gone through some biblical hot aches in my feet earlier in the day, the sun felt like the touch of God, and despite not being religious, I offered up a genuine prayer thanking whoever was up there for the sun. Obviously whoever it is has a sense of irony, because as soon as the prayed ended, the sun disappeared and a mini storm rolled in. The summit ridge was encased in clouds/wind and visibility dropped. James took the lead and ploughed through endless snow, reaching a point where the summit was only 70m away and 10 meters higher than them according to the map. I took over again to finish off. However, 30 minutes later, we were still going uphill, far past where the summit was marked on the map. Just wanting it to be over, I started to get paranoid about any other sneaky obstacles the mountain might throw in the way. At 4pm, out of the mist, a steep cornice-looking thing reared out of the mist ahead of us, looking like another two pitches of climbing were necessary! Completely unwilling to do any more climbing and with terrible visibility, we threw up the bivy tent right below it and jumped inside it to wait out the bad weather overnight. I’m not sure how he found the energy, but James fixed a pitch up the cornice that evening. We shivered the night away, barely able to eat and just focused on keeping all the extremities as warm as we could.

Day 8 arrived with clear, calm weather, and a single cliff bar to share for breakfast (five days of food, remember). It turned out the cornice thing was the summit, and after we touched it with the safety of a belay (measured at 6673m on a Garmin), thoughts turned to getting off the mountain.

Very little of the planned descent route had been visible from the valley in the previous weeks, and bad weather had meant that recce missions to scope out the descent were of limited utility. However, tough descents are where James really starts to shine. After we got as much information as possible from the summit ridge, we started to abseil, first off rock then off endless V-threads. After some complex glacial crossings, abseiling over seracs, more rock, then more V-threads, we eventually reached a bivy spot just as the sun set, in time to see the massively comforting sight of headtorches shining up at us from base camp. Akbar had made sure to shine a light at us on the mountain every night at 7pm, which had done wonders for our morale over the route. We ate the last of our mashed potatoes and split the last of our remaining rations for what we hoped to be the final day, exclaiming about how thick the air felt at 5000m.

Day 9 we continued down to a large rock rib/ridge between two glaciers that converged at the base of the mountain. Seeing no good way through either glacier, we started abseiling down the rib, aiming for the convergence point of the glaciers. At the final abseil, looking into the debris-strewn field below them, we came up with a plan to race through the glacier on climber’s left – it was the more passable of the two, but threatened with huge seracs above. Completing the final abseil, we roped up and climbed onto the glacier, did two speed abseils leaving screws behind, reached the base of the glacier, walked 200m to the right behind a rock rib and were done! Feeling thrown off by the lack of risk, we walked across a frozen pond on the way back, and before reaching base camp were greeted by a rowdy, chanting mob consisting of Adnan, Najeed, Gemma and the shepherds who were happily firing rifles off into the air. They wanted to name the mountain ‘James Chhok’ (James mountain), as James had done such a good job at international relations, but he convinced them to name it ‘Akbar Chhok’ instead.

There are many people to thank for this trip – Mountain Equipment, Petzl and La Sportiva for gear supplied, the Alpine Club, the Mount Everest Foundation (MEF), the British Mountaineering Club (BMC) and the Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC) for assisting with funding, Tom Livingstone for setting up the YAG and bringing us all together, James for the wealth of experience he brought to Pakistan, Hassan, Adnan and Najeeb for allowing us to stay in Hostel Nomads and for joining us for the trip, and most of all Akbar and the rest of the Shepherds who kindly let us stay with them for our duration in the mountains, provided us with food and shelter, and kept an eye out for us while we were in the mountains.

- George Ponsonby, Ireland

Copia link

Copia link

See all photos

See all photos