The children of Fessura Kosterlitz: the legendary crack climb in Valle dell'Orco

1 / 4

1 / 4 Maurizio Oviglia

Maurizio Oviglia

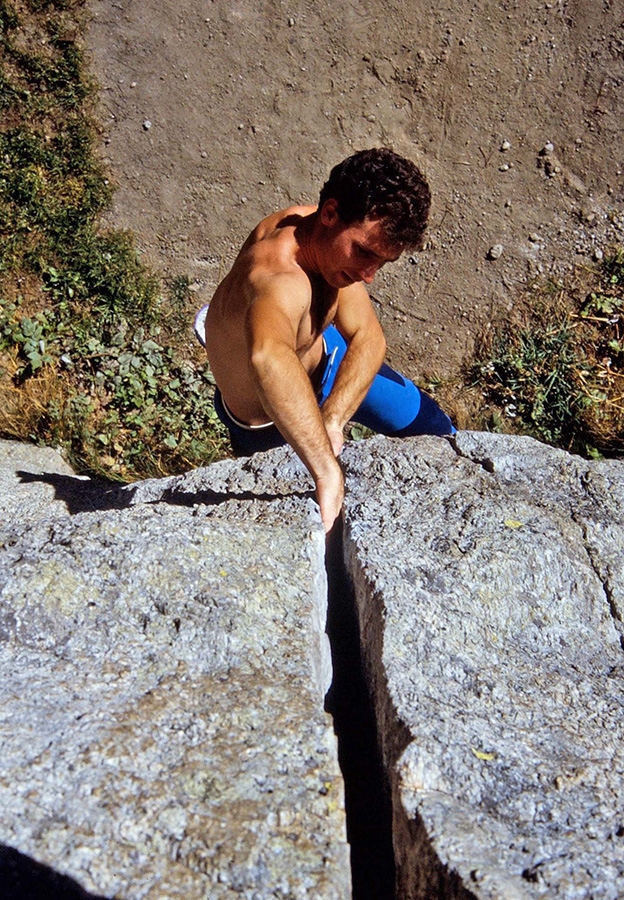

We didn’t know who Mike Kosterlitz was. We certainly didn’t suspect he was a research physicist, and we certainly weren’t even aware of his mountaineering activities, of his new routes on Pizzo Badile or up other famous alpine faces. But we knew about the crack, his crack, referred to as Fessura Kosterlitz. A vertical and perfect crack, just over 7 meters high, situated just below Ceresole Reale in Valle dell’Orco.

Had it been in the USA, then the Kosterlitz crack may well have gone by totally unnoticed, but in Italy it had become famous thanks to its slightly overhanging start and width that initial fits only very small hands. For everyone else it was either too narrow to fist jam properly, or too wide to finger lock. At the same time, it proved so elusive and flared that it couldn’t be laybacked, at least not without difficulties far harder than the VII grade put forward by the first ascentionist in 1972. This was probably the first grade VII in all of Italy.

In short, the Kosterlitz crack had to be climbed head on, by jamming upwards, using a technique and an art which very few had mastered. And it needed to be climbed right to the top, without a rope and without crashpads, as was the standard back then. Nowadays it would probably be called a "highball", that is, a very tall boulder problem requiring a number of spotters and a bundle of crash pads stacked one on top of the other.

But back in the day when I started climbing, i.e. in the early eighties, there were no free lunches. Either you climbed to the top, or you fell down to the ground. If you wanted to you could give up and jump down from where it was still possible to do so without breaking your bones. Dare up or jump down, that was a question only you could answer, in a matter of split seconds. If someone happened to be there with you, almost never did they cheer you on or spot you. In utter silence it was up to you to decide whether or not to push into a zone from where a fall would have consequences. This is why the climbers from Turin and the surrounding areas were split into two groups: those who’d climbed it and those, far more numerous, who had attempted the crack but failed. Fessura Kosterlitz became an icon, a status symbol comparable to the grade 8a a few years later. A legend, a desire destined to remain a dream for most climbers.

Like many climbers of that era, climbing the Kosterlitz crack became an obsession. Fortunately, the first indoor gym in Italy was opened at the time, Palazzo a Vela in Turin. Built in concrete, on the right it featured a prominent roof with some hand cracks exactly the same size as the famous Kosterlitz crack. Mere chance? Or astute marketing? After an entire winter training on the concrete model, I finally managed to climb the original crack. The price however were some scars on my hands, visible even today. Yes, because even the precise position of the scars, located between thumb and index finger, indicated if you were really using the right technique or not! We didn’t have tape back then, we’d only seen some Americans use it, and jamming gloves hadn’t been invented yet. Meaning that before healing the wounds and scabs remained for weeks and sometimes months on end…

I could tell a thousand stories about the Kosterlitz crack. My climbing partner, for example, was even capable of climbing the crack the opposite way round, ie, with his shoulders against the boulder. He jammed one hand into the crack, lifted his feet off the ground and then made a full rotation. One day in winter though he underestimated the final moves, the top was covered in snow and he fluffed up the mantle. Falling right down in front of us he broke both ankles. Shortly afterwards we all went to the bar at Noasca and he crossed the road on all fours, as if he’d done nothing more than twist his ankles… But to be a member of the club of "those who’ve climbed the Kosterlitz" of course it didn’t suffice to have climbed it once only. You had to be able to repeat it over the years! And so, over the course of these 45 years, someone has always attempted the crack, even some of us veterans. Gabriele Beuchod is said to have mastered it in his Clarks, the iconic suede shoes better suited for the city than for a crack. It was felt that perhaps it was easier like this, because he could jam his feet in better. So one year, annoyed by the fact that I couldn’t even get off the ground, I took off my shoes and climbed it in socks! Perhaps it was easier like that, but the pain was unbearable! Perhaps I was the first climber to have scabs on both hands and feet?!

As it is well known, the Kosterlitz boulder risked being completely destroyed when a tunnel was built nearby. It was saved in the nick of time thanks to a petition promoted by climbers. Nowadays half of the boulder has been swallowed up by the tunnel’s cement, but the crack has been saved. A piece Italian climbing history, written by an unknown Scottish physicist, out there for all those who wish to give it a go.

by Maurizio Oviglia

Copia link

Copia link