Alexander Huber interview

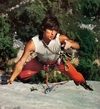

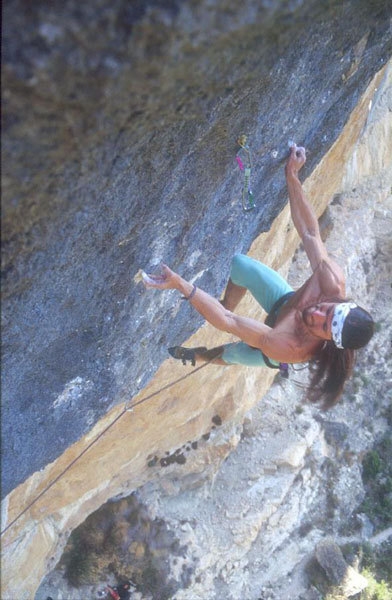

Alexander Huber is widely recognised as one of the best climbers in the world. Since the start of the '90's and all the way up to present day, the 1968 born Bavarian has managed to leave his mark like few others in our vertical world: from extreme single pitches at the crag, via big walls in Yosemite, new routes in Patagonia, the Dolomites and the highest mountains in the world. Determined, rational, at times outspoken, in this interview he recounts how he lives and interprets the mountains.

Interview with Alexander Huber, October 2008

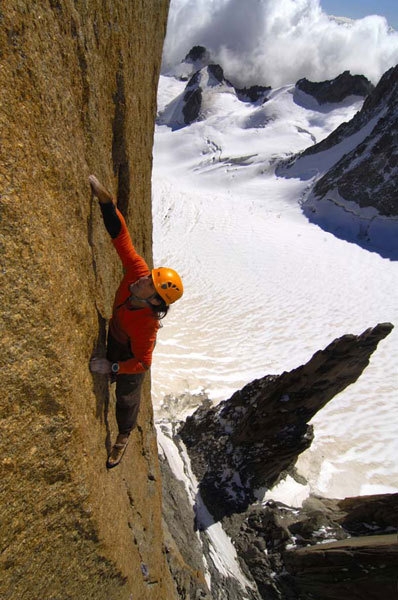

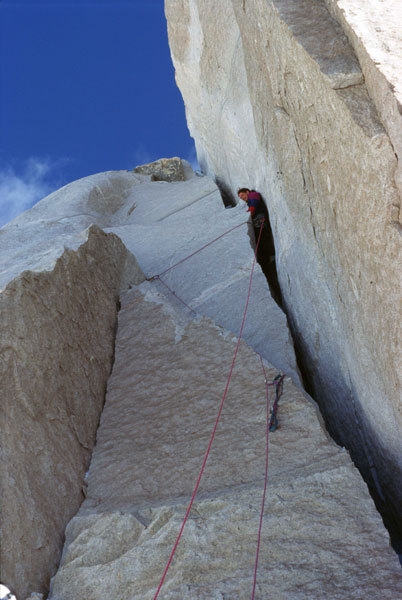

Alexander, it seems like you've got a great feeling with Grand Capucin. In 2005 you freed Voie Petit, the hardest outing on the mountain, while this summer you soloed the Swiss Route...

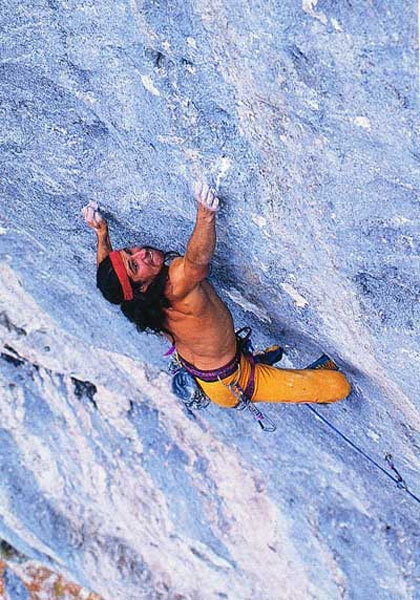

Gran Capucin isn't the highest mountain in the Mont Blanc massif, but with its first ascent via the East Face in 1951 it immediately became a sought after goal. And this above all because the granite on Gran Capucin is quite simply fantastic. It's exactly for this reason that I made my pilgrimage to this impressive granite pillar. I was further motivated by Arnaud Petit, who in 1997 carried out a first ascent on this mountain. What was missing was the complete redpoint and Arnaud mentioned I should give it a go. I didn't need telling twice. And in effect the "Voie Petit" is the hardest route on the mountain...

Where did this solo come from? Was it something you'd dreamt about for a long time, something which perhaps matured after the Dent du Géant in 2006?

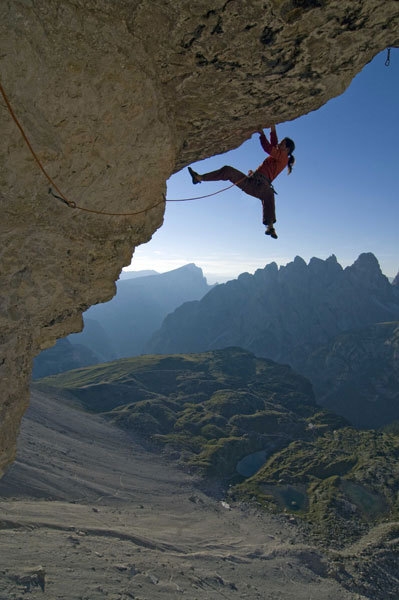

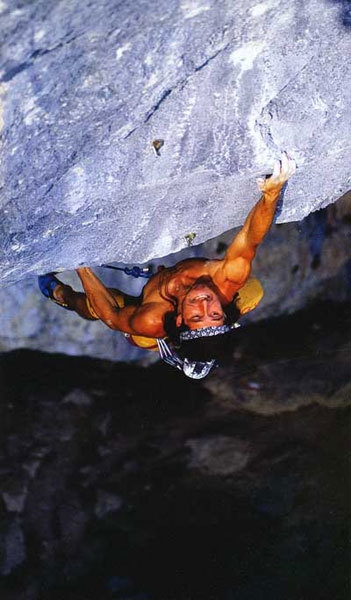

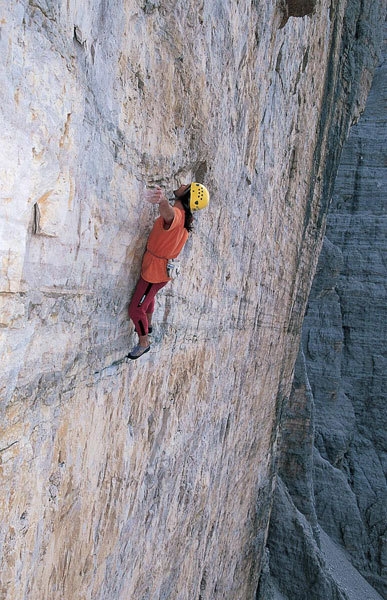

The idea had fascinated me since the very beginning, but Mont Blanc is a long way from home and this is why I only considered it seriously this year. Obviously the solo up the south face of Dent du Géant was a preparation for the Capucin ascent. I already had experience on big rock faces, such as my free solo of Hasse Brandler on the Tre Cime di Lavaredo in the Dolomites, but climbing in a high mountain environment was nevertheless something new. Weather plays a far greater role, cold temperatures make things a lot harder. Add to this the fact that, due to the snow on the mountain, when the sun shines water begins to seep down the cracks. This creates a problem which should not be underestimated and which can also be dangerous for a free solo... In my mind Gran Capucin is the logical continuation of a solo climb in a mountain environment.

Talking of solo ascents in the mountains, what do you think of Hansjörg Auer's ropeless ascent on Via del Pesce, a.k.a. The Fish route on the Marmolada?

For me this was a sensational piece of news. What surprised me most was not so much the choice of the route, but the style with which it came about. The fact that it was climbed without any particular preparation is truly incredible. Nothing more than an ascent two years previously and a quick check via abseil down the route the day before... This shows great faith in one's abilities.

I on the other hand have to say that I prepare my solo projects in a completely different manner. At the end of my preparation I know every single difficult move painstakingly well. I follow my belief: I invest as much time as necessary in my preparation until I have everything under control.

Tell us about the style you use for your multi-pitch routes?

I use bolts only there where I simply cannot continue without. The use of trad gear on limestone, compared to granite for example, is less evident. But if I'm determined and manage to find the energy to place bolts only where they are really necessary, then I'm often surprised by how high I can climb with so few bolts. For those who repeat these routes it means being in a situation which offers a true adventure: no pre-prepared "bolt lane" but plenty of, at least apparently, virgin territory.

You describe your latest creation, Sansara, as a sport route. But on the topo there are only 5 bolts in 6 pitches.

Sansara, just like my Feuertaufe, represents the non-plus-ultra of difficult sport climbing in an alpine environment. You need to be good at climbing and you have to be strong mentally. Seen from this viewpoint, the Xth grade isn't really about the physical difficulties but rather the psychological pressure you're under when you try to repeat a route without having checked it out previously from above.

Talking about adventures - this spring and autumn Yuji Hirayama and Hans Florine had some incredibly quick days on the Nose

Congratulations to Hans and Yuji! I know what it means to race up the Nose this quickly. That the record set by myself and my brother held firm only 6 months isn't a problem at all. No record is set for eternity, there will always be someone better!

Talking about eternity: this autumn Adam Ondra carried out the first repeat of your White Rose at the Schleierwasserfall, a second ascent which was in the making since 1994. What are your thoughts on this?

At present Adam Ondra is the climber who belongs not only to the future, but who also manages to contribute to the development of this sport today. Adam isn't only a good climber, he has charisma and manages to see what is important for sport climbing. I'm obviously extremely happy that he found his way to the Schleierwasserfall and that he repeated "Weisse Rose".

We all know that grades, especially those at the very top, are an enigma. How do you interpret these difficulties?

Let me give you an example: Adam confirmed my thoughts about "Weisse Rose": it's harder than "La Rambla". It's a fact that La Rambla increased in grade from 8c+ to 9a+. Often people believe this is due to the route extension, but in reality the difficulties do not change substantially with this extension. The difficulty in traversing from the Rambla belay rightwards to finish up "Reina Mora", compared to the crux on La Rambla, is not relevant. To this you also have to add the fact that La Rambla isn't harder than Action Direct and therefore cannot be harder than 9a. In 1995 Action Directe was given 8c+, that is why my routes such as "Weisse Rose" and "La Rambla" had to be given 8c+. Nowadays Action Direct is considered to be the benchmark 9a, so both "Weisse Rose" and "La Rambla" turned into 9a. And if you take Action Direct as a reference for 9a, then I believe many current top routes are considerably overgraded.

After all these years we're still talking about your routes...

Well if you use modern day parameters and you consider La Rambla as a 9a+, then consequently my Open Air should be given 9a+, too.

But don't you think that standards have risen in the meantime?

Yes, but I believe that a right step towards a hitherto unseen difficulty has only been taken now. Chris Sharma is the driving force behind all of this, his ability has always been phenomenal. I think it's a shame that these incredible performances are cast in a less beautiful light my doubtful performances of others. Sharma or Ondra - those who climb as hard as they do - manage to prove their potential not just on one amazing route, but again and again. We're not talking about a single 9a here or there, we're talking about 9a's in series! It's a truly impressive result which goes well beyond what climbers were capable of doing in the past.

Can you explain a bit better?

Nowadays people presume that "Jumbo Love" is potentially the hardest route in the world. What I find curious is that still today most magazines, without hesitating, place Jumbo Love together with Akira and Chilam Balam. Had 9b been climbed in 1995, more than a decade ago therefore, then Chris Sharma's performance seems like a kindergarten! Furthermore one has to understand clearly how long Chris Sharma's journey has been to get where he is today. And one also bear in mind what extraordinary talent Sharma possesses, and has had to use, to get where his is today. Unlike others, Sharma has proven his talent hundreds of times in the past and will do so time and time again in the future. Chris has created and earned his credibility. One thing should be clear: we all want to believe other climbers! But without this willingness I cannot believe in their ascents because the history of humanity has taught us that one shouldn't believe blindfold.

Can one have blind faith in mountaineering?

In mountaineering there are far clearer proofs. When someone returns from a summit and brings detailed information and photos, then one can believe a person's ascent. Hermann Buhl reached the summit of Nanga Parbat completely on his own in 1953 and his debrief and the photos are proof beyond doubt of his ascent. These were created not to prove something, rather they were fueled by the natural desire to capture a given moment and to remember it. Cesare Maestri on Cerro Torre and Tomo Cesen on Lhotse stand in contrast to this and offer nothing. Not only because photos are missing, but above all because of the vague descriptions which in the end say nothing more about a route which one couldn't already gleam from a photo. If you publicise such an important ascent, and if you are not ready to provide concrete information to the interested public, then the public cannot reward this behavior with its recognition!

This year Garibotti and Haley finally carried out the Torre traverse in Patagonia. You had your sights set on the same objective, together with your brother Thomas and Stefan Siegrist.

Congratulations to Rolando Garibotti and Colin Haley. They crowned a dream with their heart and their passion. We were interested in this traverse as well and obviously we would have liked to be the first. But in that moment the risks, due to the high temperatures, were simply too high. One has to remember that the mountains will always be there and the Torre Traverse still represents a dream that we'd like to achieve!

In all these years you've lived out many of your dreams, in a multitude of different vertical disciplines. Where do you feel you've risked the most?

By the very nature of things, during my free solos. Here, more than in any other discipline, you dance on a knife edge. I'm very rational: I only climb without a rope when I'm convinced I have everything under control. Compared to my solo on Kommunist (8b+, Schleierwasserfall, Editor's note) or the Direttisima on Cima Grande di Lavaredo, I'd say that my solos in the high mountains - such as on Gran Capucin or Dent du Géant - are connected to many other factors which, despite the relative technical difficulties, render the undertaking both demanding and exciting.

In 1998 you reached the summit of Cho Oyu, after which you haven't climbed any other Himalayan giants. Was the experience a bad one?

No, I simply wanted to invest more time in my climbing, to achieve some dreams I still had locked away in my heart. In the future climbing will slip into second place compared to high altitude. In the future you'll find us less in Yosemite and more in the Himalaya.

Talking about Yosemite, what springs to mind when you hear the word El Capitan?

I think back to a beautiful period in my life which this unique wall gave me, and I thank her for having been allowed to experience it.

Big wall, crags, mountains - all of these are connected by your new routes. Is this your Leitmotif?

My generation still had much to explore. The Tre Cime, El Capitan, Latok - there was still so much terrain to be discovered. Nowadays it's definitely become harder for the pioneers. But in the future there will definitely be charismatic climbers capable of reinventing climbing again and again.

We'll see what the future holds therefore. But for you personally, what's the most important thing?

I love the mountains, regardless of the grade of the difficulties. In the future I will continue to climb in the mountains, this is what is important for me. And I will continue to show an interest, give my opinion about the development of this sport.

Alexander Huber - a selection of ascents

1992: Om 9a/9a+, Triangel, Austria

1994: Weiße Rose 9a, Schleierwasserfall, Austria

1994: La Rambla, Siurana, Spagna

1995: Salathé 5.13b, Yosemite, USA

1996: Open Air 9a+, Schleierwasserfall, Austria

1997: Latok II, 7108m, VII+/A3+

1998: Cho Oyu, 8201m

1998: El Nino 5.13b & Freerider 5.12c, Yosemite, USA

2000: Bellavista 7a+/A4, Lavaredo, Dolomites. First ascent in winter

2001: Bellavista, Lavaredo. First mountain 8c

2001: El Corazon 5.13b, Yosemite, USA

2002: Hasse Brandler, Lavaredo, Dolomites. Solo

2003: Opportunist 8b, Schleierwasserfall, Austria. Solo

2003: Zodiac 5.13d, Yosemite, USA

2004: Kommunist 8b+, Schleierwasserfall, Austria. Solo

2005: Voie Petit 8b , Grand Capucin, Mont Blanc

2006: Golden Eagle (V 5.11 A1), Patagonia

2007: Pan Aroma 8c, Lavaredo, Dolomites

2007: The Nose Speed Record, Yosemite, USA. 2:45:45

2008: Swiss Route, Gran Capucin, Mont Blanc. Solo

| Links Planetmountain | |

| News Alexander Huber | |

| El Corazon, Yosemite | |

| Golden Gate, Yosemite | |

| Links www | |

| www.huberbuam.de | |

1 / 13

1 / 13

Copia link

Copia link

Heinz Zak

Heinz Zak

See all photos

See all photos