Repairers of the fragile mountain environment

1 / 5

1 / 5 M. Nesa - www.guidealp.it

M. Nesa - www.guidealp.it

The temperature in the Alps rose approximately 2°C in the 20th century, compared to an average of 1°C in the surrounding areas. Heavy rainfall is increasingly frequent and the permafrost (the ice contained in the rock or between the debris) continues to melt, causing floods and landslides. Furthermore, the rise in temperature triggers change in vegetation and also conditions agriculture and forestry, threatening Alpine biodiversity as a whole. Climate change is just one of the critical issues affecting the mountains, which include excessive exploitation of the soil, urbanisation, fires, deforestation and, most important of all, depopulation. These aspects highlight the contradictory nature of this fragile environment, threatened by both the excessive presence of man and his abandonment. Even the people charged with looking after the mountains have changed: farmers-breeders have given way to the institutions which, in turn, commission companies specialised in the construction industry.

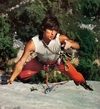

The action taken to "repair" the mountains is very varied: it ranges from restoration and consolidation of the mountainsides to water management involving bioengineering techniques. Alpine guides are often employed by these companies as, thanks to their training and experience, they are able to carry out the most difficult jobs like working on cables and intervening when mechanical means are not an option.

What often distinguishes those who do industrial rope access is where they come from.

One of the first companies in Italy to work in this particular sector at the end of the ’70s was the Consorzio Triveneto Rocciatori: it is still a leader in its field, employing around fifty people and is also specialised in the production of rockfall and avalanche barriers. Narciso (Narci) Simion is an Alpine guide and works for the Consorzio Triveneto Rocciatori. "When I started working thirty years ago" says Narci Simion, "I managed to juggle my job as an Alpine guide with that of rock-climber/worker, but the consortium gradually took up more and more of my time. I still take clients on expeditions, although only occasionally. I am currently the prevention and protection manager at the consortium and am also part of the Research and Development team". Although all the staff at the consortium are highly qualified and experienced, there is always an element of risk to the job and Narci is well aware of this: "In highly exposed vertical environments, our workers take great care and know full well that even the smallest mistake could have serious, if not fatal, consequences. This is why there are so few accidents. In challenging but not vertical environments, on the other hand, it is easier to come away with minor injuries. The skill of a worker is often dictated (or at least it was in the past) by where he is from: if they are mountain folk born and bred, they usually have that intuition and care towards hidden dangers on site which life in the mountains teaches you". Many jobs call for special attention, as Narci explains: "Some of the more dangerous things we are asked to do include deforestation on rock faces, the removal of large boulders from slopes using pistons and loading and unloading material with the helicopter on inaccessible slopes". Companies like the Consorzio Triveneto Rocciatori are always on the lookout for qualified workers and this is a great opportunity for youngsters looking for work but, as Narci points out, the job is not for everyone: "Our work is athletic, tiring, you are always outdoors at the mercy of the elements. Some jobs take us far from home where we have to live in hotels (not five-star) and you miss your private life, especially at the end of the working day. Despite this, on the whole it is well paid and gives you a chance to see new places and meet new people, if that is what you're interested in".

There are around sixty companies in Italy which provide the same services as Consorzio Triveneto Rocciatori and they employ approximately 1100 people (regular employees and hired workers).

Then there are several teams of craftsmen and mountain guide associations, which mainly carry out the smaller jobs. In Novate Mezzola, at the foot of Val Codera in the province of Sondrio, on the border between Val Bondasca and Val Masino, we find Gualtiero Colzada. Colzada is also an Alpine guide (he is the director of the guides and the School of Alpinism in Valchiavenna) and has extensive experience of working on cables: "This work takes up about a quarter of my time. It is tiring and I don't mind doing it every so often when work as a mountain guide is slow" says Colzada while he is on duty with the helicopter rescue services. "We get called out on a variety of jobs: sorting out pathways and via ferrata, removing loose material from slopes in quarries or on rock faces over roads or houses, fixing rockfall nets, taking engineers out to sites destined for land reclamation. Our work sometimes takes us into towns where we check, reinforce and clean bell towers, buildings, silos. We also run training courses for workers in the sector and in the past we have even pruned large trees". The work often involves masking and environmental restoration but, in Gualtiero Colzada's opinion: "such projects are still very much dependent on the awareness of organisations and designers".

GOOD FOR ALPS

Magazine di AKU trekking & outdoor footwear

27/03/2014 - Shepherds and Alpine guides. Worlds apart?

| Expo.Planetmountain | |

| Expo AKU | |

Copia link

Copia link